The Costs of Bat Decline

Can we afford to lose bats? A recent study by Eyal Frank of the University of Chicago reveals that the dramatic decline in U.S. bat

Modern bats face a serious housing shortage. Millions of homeless bats have died when their caves were destroyed or converted to exclusive human use, not to mention when old-growth forests were logged. Often, the single most important action we can take to restore bats today is to provide alternative homes.

We know from long experience that desperate bats often readily occupy human-made structures, from abandoned mines and railroad tunnels to old buildings. Though building backyard bat houses is an excellent way to help, sometimes it is very much in our mutual interest to provide long-lasting structures that can accommodate large numbers, not only for pest control, but also for the pure entertainment large colonies can provide.

When J. David Bamberger was first introduced to an evening emergence of the millions of Brazilian free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) at Bracken Cave in the Texas Hill Country, he was awestruck. He fell in love with this wonder of nature and soon began asking if it would be possible to attract a miniature Bracken colony to his ranch. Undaunted by an absence of caves, he asked me about the feasibility of “building” a cave. Would bats come?

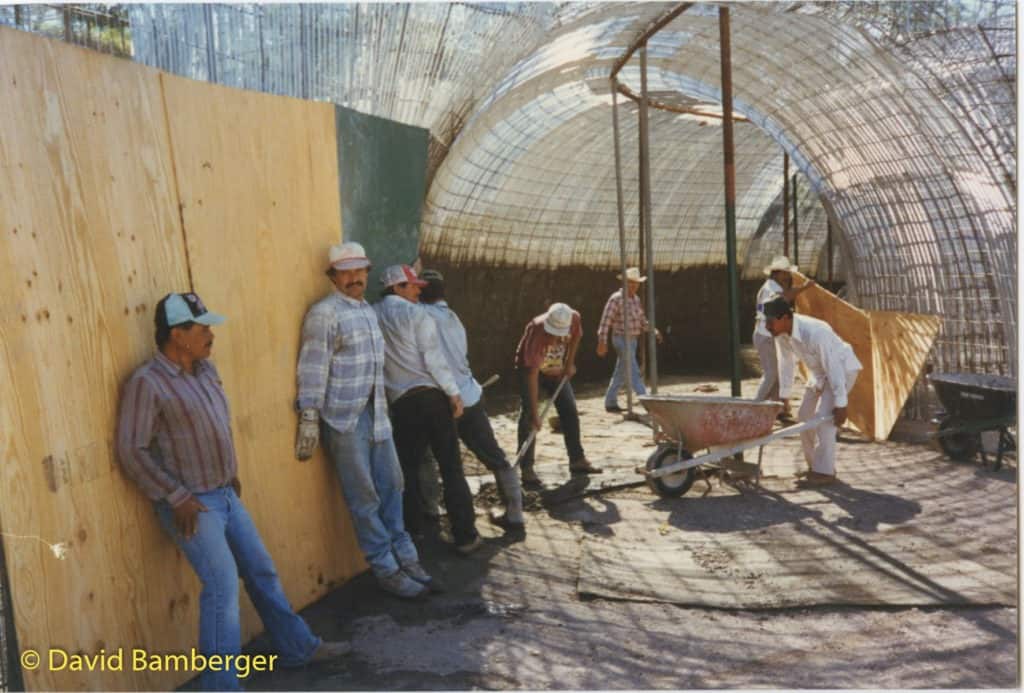

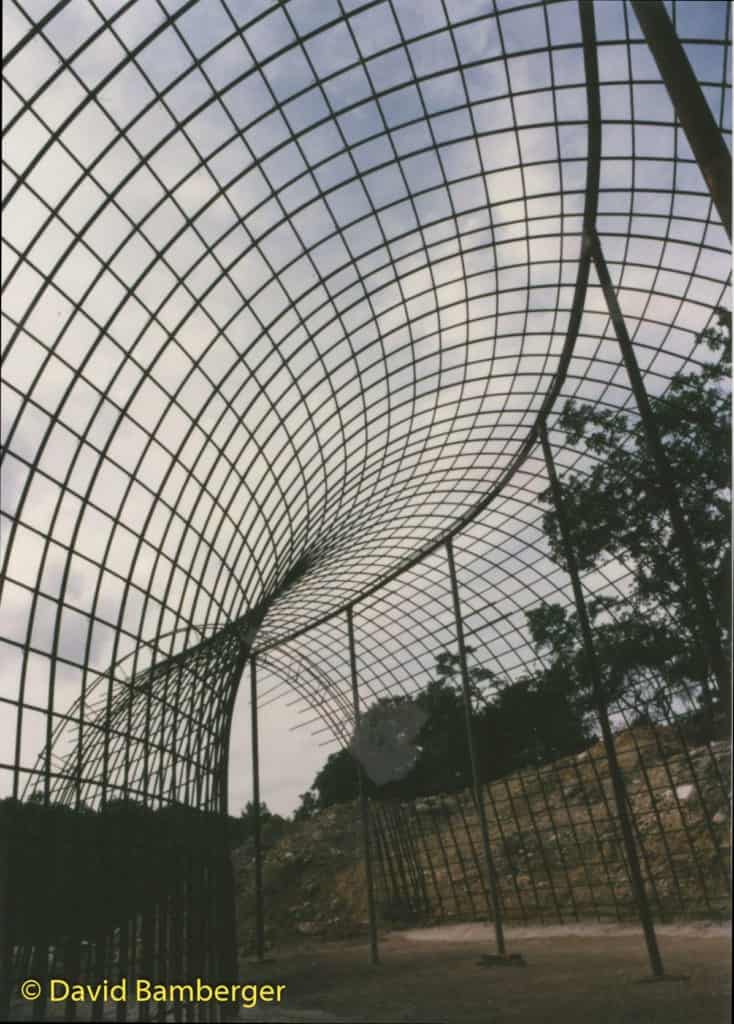

Knowing that such a project could prove costly, I was reluctant to promise success but noted that numerous abandoned mines and tunnels had attracted large bat populations. It seemed nearly certain that a cave made-to-order to meet free-tailed bat needs should be a big success. As the founder of Church’s Fried Chicken, Mr. Bamberger had the needed resources and a 5,500-acre ranch. Feeling reasonably confident of my understanding of bat needs, I offered to help. He recruited an industrial design engineer, Jim Smith, who quickly became fascinated, and began to convert my knowledge of bat needs into structural reality, a bit more than any of us anticipated! Twenty tons of rebar and 300 cubic yards of gunite (12 inches thick), a type of concrete used in making swimming pools. And it all had to be located in a ravine where it could be covered over with earth and vegetation, while allowing for natural drainage.

I advised that these fast-flying bats would want a large entrance and spacious interior with domed ceilings and lots of roughened, but not sharp-edged surfaces to provide safe footing for their pups. We provided a curving entry passage approximately 15 feet tall by 12 wide and 30 long, leading to a main roosting chamber 43 feet in diameter and 20 feet tall with a domed ceiling. Then a slightly smaller passage led to a smaller second room intended for cave myotis (Myotis velifer) who do not require such large dimensions. Initial experimentation proved costly, but Bamberger’s estimated cost to replicate the final design was $50,000 (in 2003 dollars).

The entry passage needed to curve just enough to block direct sunlight, which could increase risk from hawks and other bat predators. In case of overheating, we even included adjustable vents. We also hung several about two-foot-wide, wooden bat houses with 3/4-1-inch wide roosting crevices in the main room, in case the first arrivals might be extra choosy about their security. My reasoning was that once a core colony accepted the site, that others would be attracted to join them, gradually spreading out across all or most of the roughened gunite surfaces.

The new “chiroptorium,” as Bamberger called it, took approximately seven months to design and build, due to lots of early experimentation. It was completed and covered in earth, with vegetation planted by August 1998. Prior to being covered the inside temperature sometimes rose as high as 121 degrees F, but once protected by soil, it dropped to 88 degrees, ideal for mother free-tailed bats. By mid-October 15 cave myotis and a single free-tailed bat had arrived. Several hundred arrived the following year, several thousand the next.

Suddenly, one summer evening in 2003, Bamberger looked up to see a great column of free-tailed bats, later estimated at 200,000, and was amazed to discover they were emerging from his chiroptorium. From then on the colony quickly grew, and based on area covered and average clustering density, likely approached 500,000 when I personally entered to photograph the colony on July 29, 2016. We originally designed the structure to shelter up to a million, and several lines of evidence suggest that occupancy sometimes reaches that number, including a few weeks earlier in 2016 prior to the young learning to fly. Several thousand cave myotis have also been spotted using the smaller inner room.

Whenever I see construction materials for sale, I can’t help but wonder which new discoveries might now be available for enhancing construction at reduced cost. Lots of bats still need homes, so I’m hopeful that the Bamberger chiroptorium is just the first in a long line of improved designs. Countless large bat caves have been lost permanently to limestone quarrying, highway and housing construction and to commercialization. However, we’ve repeatedly seen how large populations can rebuild, and recent discoveries demonstrate likely cost-effective returns in crop protection, guano harvesting (for fertilizer) and ecotourism. Mr. Bamberger’s bats migrate south for the winter, making guano harvest practical without harm to his bats. And he intends to replace use of commercial fertilizer in his pastures with “home-grown” natural fertilizer in the year ahead.

J. David Bamberger’s chiroptorium is a perfect fit for his long-term goals. He purchased the worst piece of over-grazed ranch land he could find in 1969 and named it the Selah, Bamberger Ranch Preserve. Located in Blanco County, deep in the Texas Hill Country, the land was overgrown in Ashe juniper and lacked running water. Bamberger’s goal of using his wealth to demonstrate how even the most damaged land could be restored, has been a monumental and award-winning success. Today, having replaced countless acres of water guzzling juniper with native grasses, he has year-round flowing springs and a dramatic return of wildlife, including two species of endangered songbirds.

His workshops and nature tours for children, fellow ranchers and the scientific community are based on well-established fact, not on computer models. He’s truly passionate about inspiring visitors for a better future, and the chiroptorium is now his centerpiece and favorite attraction.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Can we afford to lose bats? A recent study by Eyal Frank of the University of Chicago reveals that the dramatic decline in U.S. bat

Bats are among the most fascinating yet misunderstood creatures in the natural world, and for many conservationists, a single experience can ignite a lifelong passion

Many bat conservationists know that Kasanka National Park in Zambia is an exceptional place for bats, but it is also the place that sparked my

The Kasanka Trust is a non-profit charitable institution, which secures the future of biodiversity in Kasanka National Park in Zambia. They welcome internships for students

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.