Challenging torrential rains countered by cooperative bats in Costa Rica

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Braniff flight #542 from Washington Dulles touched down at Aeropuerto Internacional de Maiquetia “Simón Bolívar,” on a muggy December evening in 1966. The passengers poured from the clamshell door down the airstair to the sizzling tarmac. A winsome bearded young man with horn-rimmed glasses and slicked back hair exited the plane, clutching the strap of his new movie camera. By his side was Claudette, his wife, a petite Jackie Kennedy look-alike. The couple were joined by Fred and Virginia Harder, also young, fit, and exuberant. This was the core team for Year Two of the Smithsonian Venezuelan Mammal Project.

Claudette and Merlin Tuttle were returning to Venezuela to resume the fieldwork they had left unfinished five months earlier. Claudette recruited her brother and sister-in-law, Fred and Virginia, to assist on the project for their final year of field work before going to graduate school.

Smithsonian curators had known Merlin since he was in high school. The 17-year-old had talked his mother into driving him from their home in Tennessee to DC so that he could discuss his observations of gray bats that lived in caves near their home. One of those scientists was Charles O. Handley, Jr., curator of mammals, who later would call Merlin “a born collector.”

Just as Merlin was finishing his undergraduate degree in zoology, Dr. Handley at the National Museum of Natural History offered to hire him as co-director of a two-year collecting project in Venezuela. When he accepted, Handley immediately asked, “Does this mean I get Arden too?”

Arden was Merlin’s younger brother. The brothers were a collecting dynamic duo, gaining expertise during summers in Mexico and Peru, working for the American Museum of Natural History, in addition to collecting in the hills of Tennessee where they grew up.

May 30, 1965, Claudette and Merlin graduated from Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Michigan. In early June (Merlin forgot the date) they were married and soon departed for Washington, DC to prepare for Year One in Venezuela.

The project purpose was to collect mammals and their ectoparasites. Merlin would lead the expedition, Claudette would be in charge of collecting ectoparasites, and Arden would help with mammal collecting and preparation for Year One. Then he would take a year off to return to Andrews University as a pre-med student.

On July 18, 1965, they flew to Caracas.

At the time, the United States had mobilized troops to Vietnam, and Merlin’s draft number was called for induction. However, Dr. Handley had obtained a one-year deferral for Merlin.

While working the first year on the project in Venezuela, from July 1965 to July 1966, Merlin’s one-year deferral expired. The Smithsonian’s personnel director, Joseph A. Kennedy, wrote to the Tennessee Local Board No. 50 Selective Service System, that Merlin had become “indispensable” to the project and asked for a one-year extension.

On June 23, 1966, Handley sent Merlin a letter advising him that there was no reply from the draft board and that there was nothing more he could do. It would be wise to close his affairs in Venezuela in a manner easy to clear up in case he wasn’t able to return.

On July 20, 1966, Merlin and Claudette left Venezuela and flew to Washington, DC to wait and see if anything further could be done. Arden was left in charge in Venezuela, while Merlin was gone.

Not knowing from one day to the next if the Smithsonian’s request for his draft deferment would come through, he preoccupied himself at the museum with creating a dichotomous key for the mammals of Venezuela.

Meanwhile, the personnel director at the Smithsonian made requests to Merlin’s home state of Tennessee and to the Director of the Selective Service, General Hershey. The general replied that he couldn’t override the State of Tennessee but suggested they request a presidential deferral. President Lyndon Johnson had just announced that he would not grant any more deferments, so this was a long shot.

It was granted.

The second year team grabbed a taxi for the 45-minute drive from the Maiquetia Airport to Caracas. En route, Merlin noticed their driver was meandering down side roads, and so he told him he knew how to get to the Park Hotel, and this was not a direct route. The taxi driver said, “It’s like the wild west here now,” with gun fights on the streets of Caracas between Venezuela’s National Guard and the Communist guerillas. To Merlin, the jungle was a safer place than Caracas, and he was determined to get back to collecting as soon as possible.

They safely arrived at the Park Hotel and headed directly to the Museo de Ciencias Naturales to organize the field gear Merlin had left in a storage room, per Handley’s instructions.

Several days into their preparations, a visiting Smithsonian taxidermist, conducting training to museum employees, was beaten and robbed at gunpoint by Communist insurgents. His guns were stolen. This happened 75 feet from the storage room where the Tuttles and the Harders were preparing for their year-long expedition to the interior Amazonas Territory. Meanwhile, their guns were broken down in pieces and hidden in waste baskets.

Merlin and Fred, an accountant, had budgeted $20,000, based on a bid from a private air carrier to fly multiple missions, carrying their equipment to a remote savannah at a small mission outpost called La Esmeralda in the Amazonas Territory. The Smithsonian transferred the money to a bank in Caracas, but Tuttle didn’t pay a dime for air transport. He used his Letter of Introduction to obtain free transport via the US Embassy, which ordered a C-47 navy plane, after apologizing that it would take a week to get due to the shortages caused by the Vietnam War.

Illustrative of the lawlessness in Caracas at the time, all of the banks had hired armed guards stationed behind sandbag barriers at entrances. Over a week’s time, expedition members hand-carried approximately 90,000 Venezuelan bolivars from the bank, packaged to look like Christmas gifts. These presents were stored in false bottoms of expedition trunks kept at the museum. The cash would be used to pay indigenous workers for the specimens they collected.

I asked a Panamanian friend, Brittmarie Janson Perez, who worked as a political analyst for the US government at the time, about the political climate in Caracas. She recalled,

“Venezuelan guerrillas, strongly influenced by Fidel Castro, were engaged in an armed “revolutionary struggle” comprising both urban and jungle operations led by legendary Communist leaders. I spent a lot of time reporting on the Communist leaders, some of whom later abandoned violence and took part in the political scenario. I think one or two are still alive, opposing the current dictatorship.”

Brittmarie Janson Perez, Political Analyst

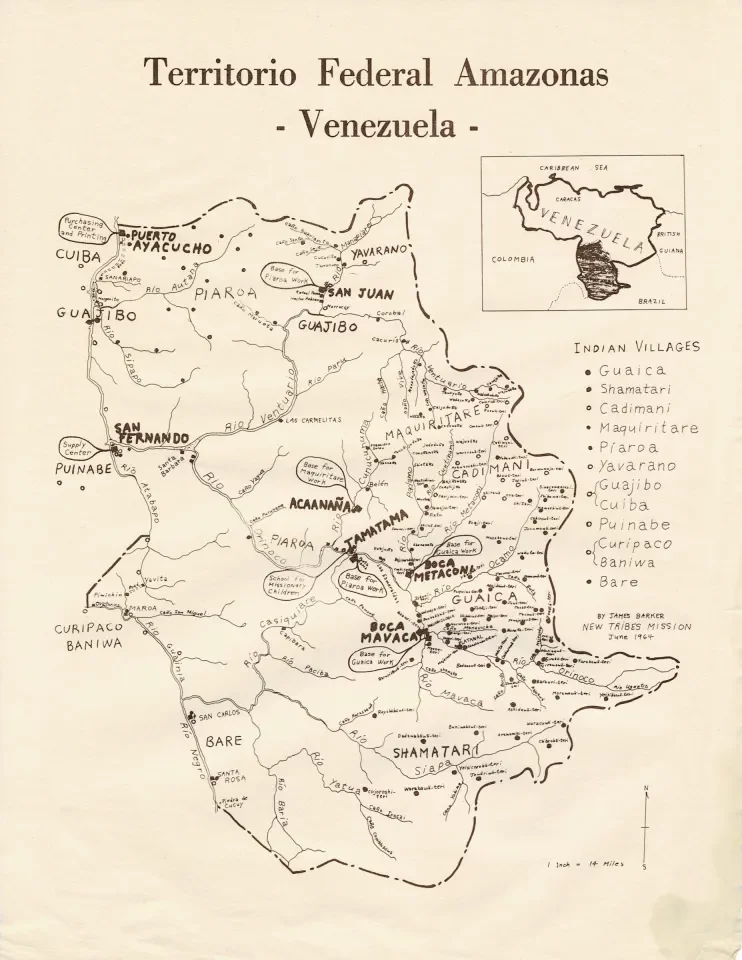

Two 50-ft-long dugout canoes, each carved from a single tree by the Maquiritare, were waiting on the Rio Orinoco. Merlin had pre-ordered them six months in advance via the New Tribes Mission, an evangelical Christian group specializing in converting the indigenous people.

With their decades of experience in the Amazonas Territory, the missionaries’ advice and logistical connections were invaluable. They organized the shipping of thousands of gallons of gasoline up the Orinoco from Puerto Ayacucho in 55-gallon drums, along with other supplies they stockpiled at their Tamatama headquarters in anticipation of expedition needs.

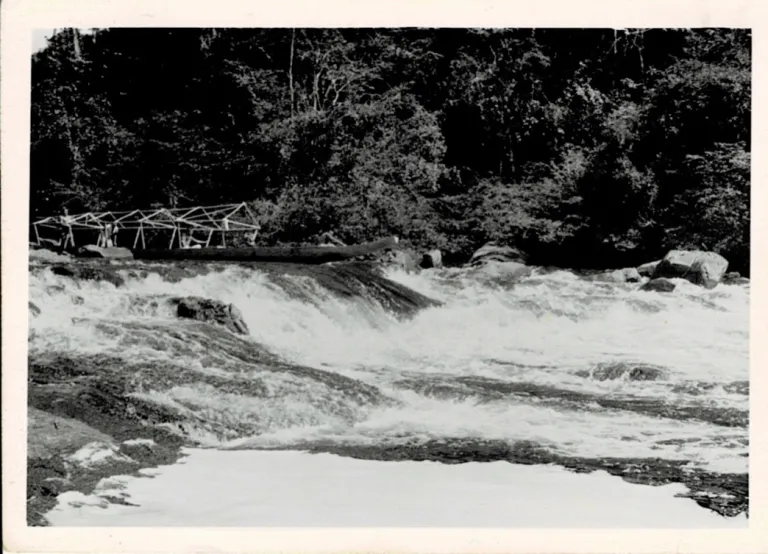

Expert river men sent by the missionaries loaded equipment and supplies onto the canoes, carefully distributing the weight evenly in anticipation of white water challenges.

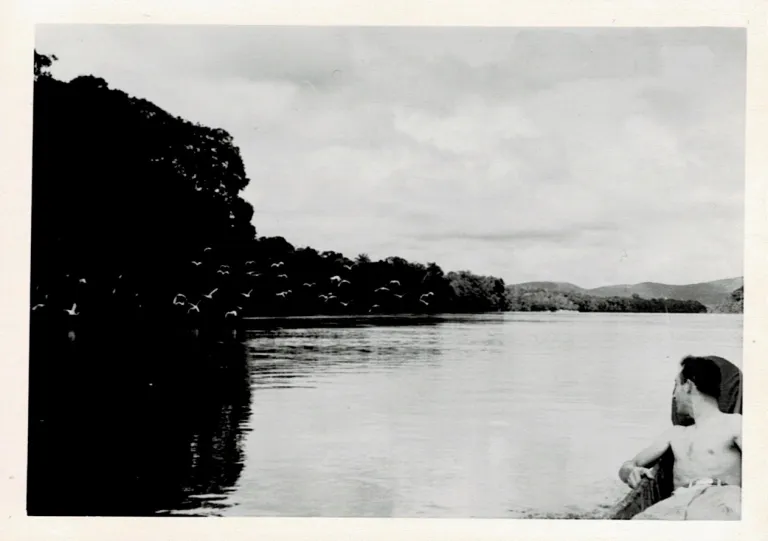

Floating down the Orinoco, the main river of Venezuela, the weary travelers finally relaxed in the welcome breeze that denied the ubiquitous biting gnats a meal.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Bats can use sounds in many complex ways. They can sing and even have different dialects… When imagining a bat, the first thoughts that come

It was a long road to Austin, Texas. More than five years after my first introduction to Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation as a teenager, I packed

TEDx Talks recently released the video of Merlin Tuttle’s fascinating presentation about bats at TEDxUTAustin’s seventh annual conference, held on March 23rd. During his presentation,

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.