Challenging torrential rains countered by cooperative bats in Costa Rica

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

“If our Maquiritare crew hadn’t been as experienced at piloting dugouts in such challenging conditions, everything could’ve been lost, or we could’ve drowned. It was crazy!”

Merlin Tuttle

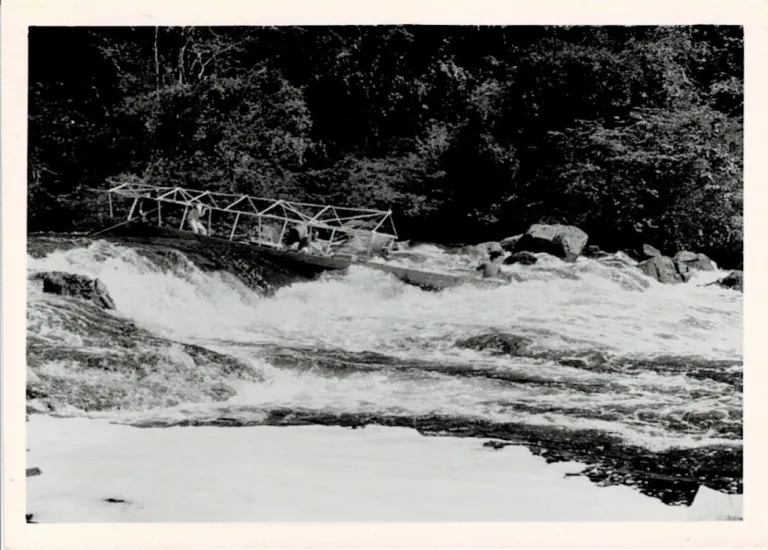

The expedition set off on the wide, calmly flowing Orinoco, soon entering the flooding, white-water Rio Cunacunuma. After seemingly endless miles of motoring against the current, through treacherous rapids and potentially deadly boulders, they finally had to unload their three 55-gallon drums of gasoline and more than a ton of equipment and supplies to portage around an eight-foot waterfall. It took all day to reach their destination: the Maquiritare village of Belén.

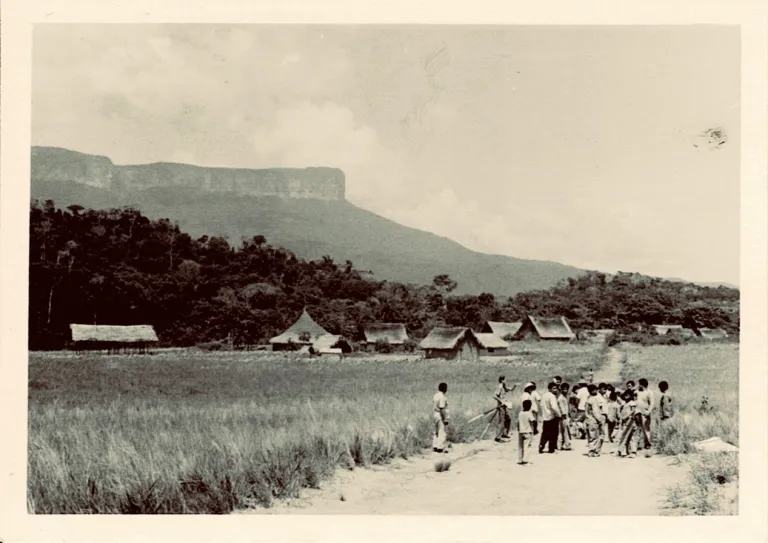

Belén was located in a savannah between two tepuis (table-top mountains), Cerro Duida and Huachamacari. Villagers welcomed Merlin’s team to establish their base camp in a large thatched structure with open sides, shielding against midday sun and allowing cooling breezes. It also provided ample area for eating, working, and storing. As an added bonus, Belén was located on a black water river, actually, a rusty red due to tannic acid from decaying vegetation. The acid apparently made the water uninhabitable for mosquitoes and biting gnats that had been annoyingly abundant pests along the white water of the Orinoco. Working and eating areas were set up, and sleeping tents were pitched nearby. It was December 30, 1966, and for about two months, this would be base camp.

The diversity of surrounding habitat provided an extraordinarily rich fauna. Belén was also ideally located at the base of one of the best access points for reaching the Cerro Duida plateau. The base camp area alone would soon yield 88 species of mammals, including 47 of bats.

Merlin could hardly wait to test his new bat trap ideas. He had seen Dr. Denny Constantine’s single-layer bat traps used to sample relatively easy-to-capture free-tailed bats at Carlsbad Caverns, New Mexico. Constantine’s trap employed over a hundred thin piano wires strung vertically in a metal frame, equipped with a plastic bag beneath. It could quickly and harmlessly capture hundreds of free-tailed bats that collided and fell into the bag. The music it made was a bonus.

While waiting at the Smithsonian for his draft board’s decision, Merlin had asked the museum workshop to make two 5 x 6-foot, collapsible aluminum frames. Each was drilled to be strung with four-pound monofilament fish line at 3/4-inch intervals. He’d also ordered two canvas bags custom-made that included plastic flaps to prevent captured bats from climbing out. Each frame was equipped with four extendable legs so it could be mounted upright in streams, trails, or other bat flyways.

Soon after arriving at Belén, Merlin enthusiastically unpacked and set one of the traps over a trail used as a flyway. Expectantly, he watched with a dim headlamp. The first two bats passed right through. He’d expected such a possibility, so he simply extended the frame to tighten the lines. An occasional bat was caught, but most now bounced off.

It occurred to him that he should try tying the two frames together, using sticks and cord to hold the two frames several inches apart, over a single bag. His idea was to tighten the lines just enough to slow bats down, allowing passage through the first set without bouncing off. Once the bats were slowed and had to spread their wings to keep from falling, perhaps the second set of lines could be sufficient to force them to fall unharmed into the bag. The modification wasn’t perfect, but with adjustment it began to catch small species that were seldom caught in mist nets. Many of the larger species still escaped by passing through both frames, but the trap soon proved indispensable for more than just catching small insect-eating species that typically avoided capture in nets.

When village hunters told Merlin about a watering hole they referred to as a “chupador de los dantas,” or drinking place of the tapirs, he was intrigued. It was claimed that the small pool of water also attracted “miles de murciélagos,” thousands of bats.

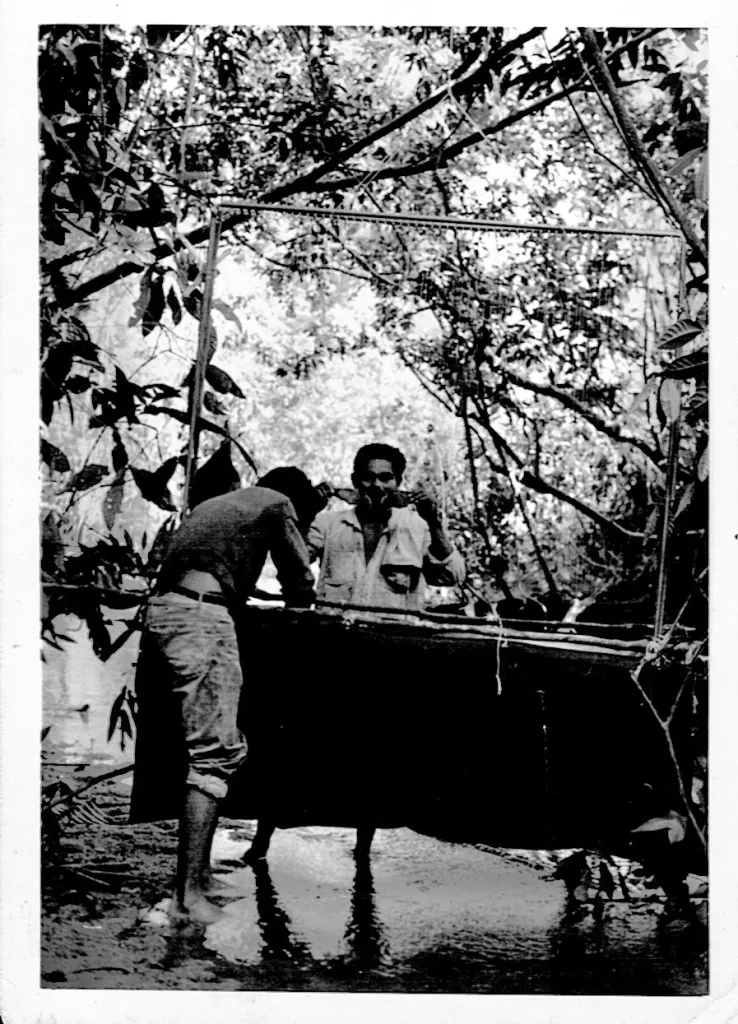

That got Merlin’s attention. Curious, he decided to investigate. He organized a day-long canoe trip up a tributary of the Rio Cunacunuma, combined with a rugged hike. It sounded like an ideal opportunity to test the usefulness of his new trap, though he also carried two mist nets.

Merlin and two Maquiritare guides arrived only an hour before nightfall. The pool was a major disappointment. Only three feet in diameter and an inch deep, it was overgrown with vines which seemed to impede any normal bat’s approach.Tapir clearly used it heavily, as trails had been cut deeply into surrounding clay.

Thoroughly disgusted, Merlin and the Maquiritare helpers made a camp nearby. They strung hammocks covered with mosquito netting beneath tarps between trees. Next, they set the trap and their two 42-foot-long, seven-foot-tall mist nets over two streams, approximately 50 feet away, one on each side of the tapir pool. No attempt was made to trap or net over the pool, since it was obviously unattractive to bats.

The mist nets were so finely threaded as to be nearly invisible. Loops at each end were threaded over freshly cut poles to tightly stretch the five main horizontal strands of each net. Adjusting the main strands allowed pockets of netting to form. Bats striking a net, would fall into one of these pockets, unable to escape.

During the night, the men took turns getting up to check the nets and trap over the streams. At one o’clock in the morning, Merlin was amazed to spot hundreds of bats flying in and out of the vines over the tapir watering hole. He excitedly rushed to awaken his two helpers, shouting “ Venga pronto! Hay muchos murciélagos al chupador de los dantas!” Come quickly! There are many bats at the tapir water hole!

As quickly as possible, they hauled the bat trap from the nearby stream to the tapir pool. Between then and morning, in less than four hours, frequently interrupted by rain, the trap caught 85 bats of five species: Tent-making bats (Uroderma bilobatum), Great striped-faced bats (Vampyrodes carracioloi) (see photo below), Heller’s broad-nosed bats (Platyrrhinus hellerii), Greater round-eared bats (Vampyrodes bidens), and Little big-eyed bats (Chiroderma trinitatum). They were all so-called “white-lined” bats because of their unique markings, also belonged to the same subfamily and ate fruit, though they were members of distinct genera, most of which were seldom captured elsewhere.

Finding such large numbers of white-lined bats at a single location was unheard of. Yet despite all the rain and available nearby streams, they were attracted to that particular, difficult-to-reach pool. In sharp contrast, the two much larger mist nets set over nearby streams, caught just eight bats in the entire night, all common species.

Merlin immediately wanted to know why. He used what he had on hand, an empty mayonnaise jar, to collect a water sample for later analysis. Unfortunately, he was unaware that the jar had to be cleaned with acid first, so the sample was polluted and of no value, and so the contents of that pool remain a mystery.

Back at base camp, a jaguar had killed two villagers, a father and son, creating fear in the community. Merlin’s Maquiritare hunter, Gonzales, and another villager tracked and shot the cat, proudly bringing it into camp. The jaguar joined other specimens in the Smithsonian’s collection.

Humid rainforest conditions meant animal specimens had to be processed quickly to prevent spoilage. Once an animal was checked for parasites, weighed, and measured, a specimen tag was attached. This tag contained the name of the collector, a unique number, the date and location of collection, and the specimen’s sex and standard measurements.

Specimens were then skinned, treated with borax, dried in the sun or in heated tents, and carefully packed in sealed containers with paradichlorobenzene crystals to prevent insect damage. At several-month intervals they were picked up by military aircraft in Esmeralda. Skulls were tagged and saved separately for shipment with the skins. Small animals were stuffed with cotton as “study skins.” Hides of large ones were tanned after shipment to the Smithsonian.

Ultimately, specimens were divided between the Smithsonian and Venezuela’s national collection where they will be protected in perpetuity. Some are only now being recognized as new species.

Such specimens may provide the only documentation of historic wildlife and the habitats they once occupied. Many of the species collected in the 1960s likely no longer exist at the locations where they were then found. They’ve fallen victim to human expansion and habitat loss.

Before animals can be studied or understood, they have to be described based on unique characteristics and given names that can be used in field keys to allow future scientists (and conservationists) to reliably identify them. A jaguar is easily recognized, but many other animals are not. A wide range of characteristics can be used to differentiate less distinctive species. For example, does a bat have a nose leaf or not? Does it have a tail or not? How long is its forearm? Or does it have unique patterns on its fur such as white stripes? A few species are only now being discovered because they differ in characteristics not readily visible, such as what kind of echolocation calls they use.

Specimens in museums provide a basis for modern research. Without them, reliable identification often would be impossible. And without such ability, a species’ ecosystem contributions or conservation needs could not be reliably determined. Furthermore, legislative or other protection of endangered species could be rendered hopeless. Merlin Tuttle, now a leading conservationist explains:

“As we become more familiar with animal sophistications, we increasingly face a dilemma—to collect or not to collect? How can we justify killing animals we love in order to save their species? This is not an easily resolved controversy. However, without specimens, often those collected long ago and preserved in museums, it might not even be possible to prioritize regions of special significance for preservation of biodiversity. Many places where we collected in the 1960s are now overwhelmed with civilization leaving our collections as the only record of historic wildlife and their needs.”

Merlin D. Tuttle

When Merlin established a base camp at Belén, he had hoped to collect on top of both of the adjacent tepuis. Surrounded by sheer cliffs, animals and plants that lived there were isolated on ecological islands that supported unique flora and fauna, including some endemic species like the Monte Duida frog.

Cerro Duida would be attempted first, proving to be an extreme challenge, so much so that plans to also survey atop Cerro Huachamacare had to be abandoned. Duida had a summit plateau covering more than 400 square miles at an elevation of approximately 4,600 feet (1,400 m), and its summit rose to 7,736 feet (2,358 m). Tuttle would spend a month in this unique environment.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Bats can use sounds in many complex ways. They can sing and even have different dialects… When imagining a bat, the first thoughts that come

It was a long road to Austin, Texas. More than five years after my first introduction to Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation as a teenager, I packed

TEDx Talks recently released the video of Merlin Tuttle’s fascinating presentation about bats at TEDxUTAustin’s seventh annual conference, held on March 23rd. During his presentation,

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.