Challenging torrential rains countered by cooperative bats in Costa Rica

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

For many years we’ve wondered just how many Brazilian free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) could cram into a single 18-inch-deep bridge crevice. Accurate counts of large colonies are difficult no matter how they’re made. However, when estimating bridge colonies, it would help if we knew the number, using an average horizontal foot of crevice.

The solution seemed easy. Two years ago, Glen Novinger, an MTBC member and I, inserted two, three-quarter-inch-thick wooden frames, each encompassing a square foot of interior space, into bridge crevices of the same width while the bats were out feeding. The idea was to later slowly remove them, forcing those roosting inside to exit into a cloth-lined bag from which we would count them.

However, the bats were full of surprises. The first night we waited patiently till half an hour after we’d seen the last ones leave—or at least that was what we thought! But when we approached to install our devices, roughly half remained inside. I couldn’t help but wonder how many emergence counts had missed those that, for whatever their reasons, didn’t emerge at sundown.

When we shined our headlamps inside, the bats at least obligingly moved aside sufficiently to permit insertion of our measuring devices. But, for the rest of the summer, they avoided those areas. By 2017, they returned. With help from partner members, Sharon and Joe Goldston, and Teresa Nichta, we photographed the bats roosting in our measuring devices.

Then we gently removed the devices. To our great disappointment most of the bats were missing! Unbeknownst to us, there were horizontal side crevices into which they escaped as soon as they detected movement of our frames.

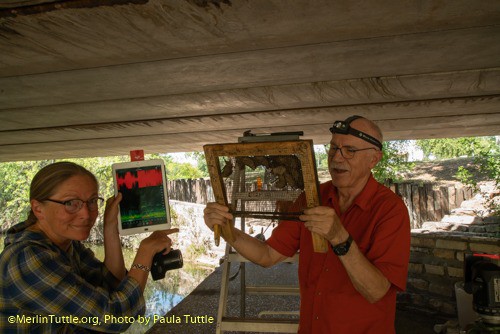

Undaunted, I added fine plastic mesh to the sides of each frame and reinstalled them after the bats left for winter. By this summer, both were continuously occupied. On September 1, long after any risk of flightless young being present, my wife Paula and I returned with Janell Cannon, a founding MTBC member and author of the book, Stellaluna. She had participated in our member bat cruise the evening before.

We again photographed visible bats. An accurate count of faces was impossible, because some retreated upward when illuminated by my focusing light. Nevertheless, there was no evidence that these bats were forming multiple layers in crevices. Sixteen bats, nearly all males, were counted from each frame. But the photos revealed that more bats roosted outside than inside the frames in identical crevice widths. The highest number visible in an adjacent 12 inches was 19.

We have documented free-tails roosting in crevices from half-an-inch to two inches wide, though three-quarters to one and a half inches wide seem to be preferred. In three-quarter-inch-wide crevices they lined up in single file. However, they formed double rows at one and a quarter to one and a half inches, at least doubling the number of bats per crevice.

Based on these results, I suggest estimating no more than 20 free-tails per running foot in three-quarter-inch-wide concrete bridge crevices, increasing to 40 in those that are at least one and a quarter-inches wide. Fifty or more are possible, though not yet confirmed, in crevices one and a half to one and three-quarters of an inch wide. These wider spaces are clearly used during peak summer build-up, though probably less earlier in the season when rearing young.

Such observations suggest that artificial roosts built to attract Brazilian free-tailed bats likely should include spaces from three-quarters to one and a quarter or possibly one and a half inches wide. Smaller co-residents of southern bat houses, such as southeastern myotis (Myotis austroriparius) and evening bats (Nycticeius humeralis), appear to prefer the smaller widths, and the first free-tails to arrive may share that preference. We’ve seen Grackles easily pluck roosting bats from crevices that approach 2 inches or more in width.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

“Just like the old days, eh Heather?” Kent softly clicks his tally counter as he sits in his folding chair on the other side of

Bats can use sounds in many complex ways. They can sing and even have different dialects… When imagining a bat, the first thoughts that come

It was a long road to Austin, Texas. More than five years after my first introduction to Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation as a teenager, I packed

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.