The Costs of Bat Decline

Can we afford to lose bats? A recent study by Eyal Frank of the University of Chicago reveals that the dramatic decline in U.S. bat

Long Cave, in Kentucky, like many others, has a long history of human occupation with little record of prior use by bats. It was mined for saltpeter, a key ingredient of gun powder, during the war of 1812 and was subject to commercial tourism, probably beginning at about the turn of the century, ending by the 1930s.

Huge passages trapped cold air and remained cool year-round, offering major opportunities for bat hibernation. Roost stains from past bat use were widespread, and the cave clearly had potential to shelter millions. As recently as 1947 some 50,000 bats, presumed to be largely the now endangered Indiana myotis (Myotis sodalis), continued to return in winter. Nevertheless, entrance barriers built to exclude non-paying tourists, increasingly restricted air flow, eventually culminating in a concrete wall and a nearly solid door.

The bat population plummeted, leaving only roost stains as evidence of extraordinary past use. By the time that Mammoth Cave National Park was established in 1941, few bats could be found in the park’s caves, and those that remained weren’t yet recognized as either important or endangered.

By the early 1990s, as characteristic bat roost stains began to be recognized, the huge historic importance of several of the park’s caves began to be suspected. Cave Resource Management Specialist and Research Coordinator, Rick Olson, invited me and several colleagues to lead an investigation. We quickly found unmistakable evidence, of past use by at least 9-13 million bats, perhaps more than twice that many, mostly endangered gray (Myotis grisescens) and Indiana myotis.

Many of the original roosts along major tour routes in Mammoth Cave could no longer be used by bats. However, we also found areas of great opportunity for restoration. Long Cave proved special. It was not connected to Mammoth Cave and wasn’t needed for tours.

Nevertheless, it wasn’t easy to convince key decision makers to approve removal of the door and concrete wall at the Long Cave entrance. A bat-friendly gate was quickly approved. But it took until 2002 for Rick Olson, Bob Currie, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist, and Ron Kerbo, a cave management specialist for the park service, to finally gain permission to remove the blockage, leaving only a bat-friendly gate.

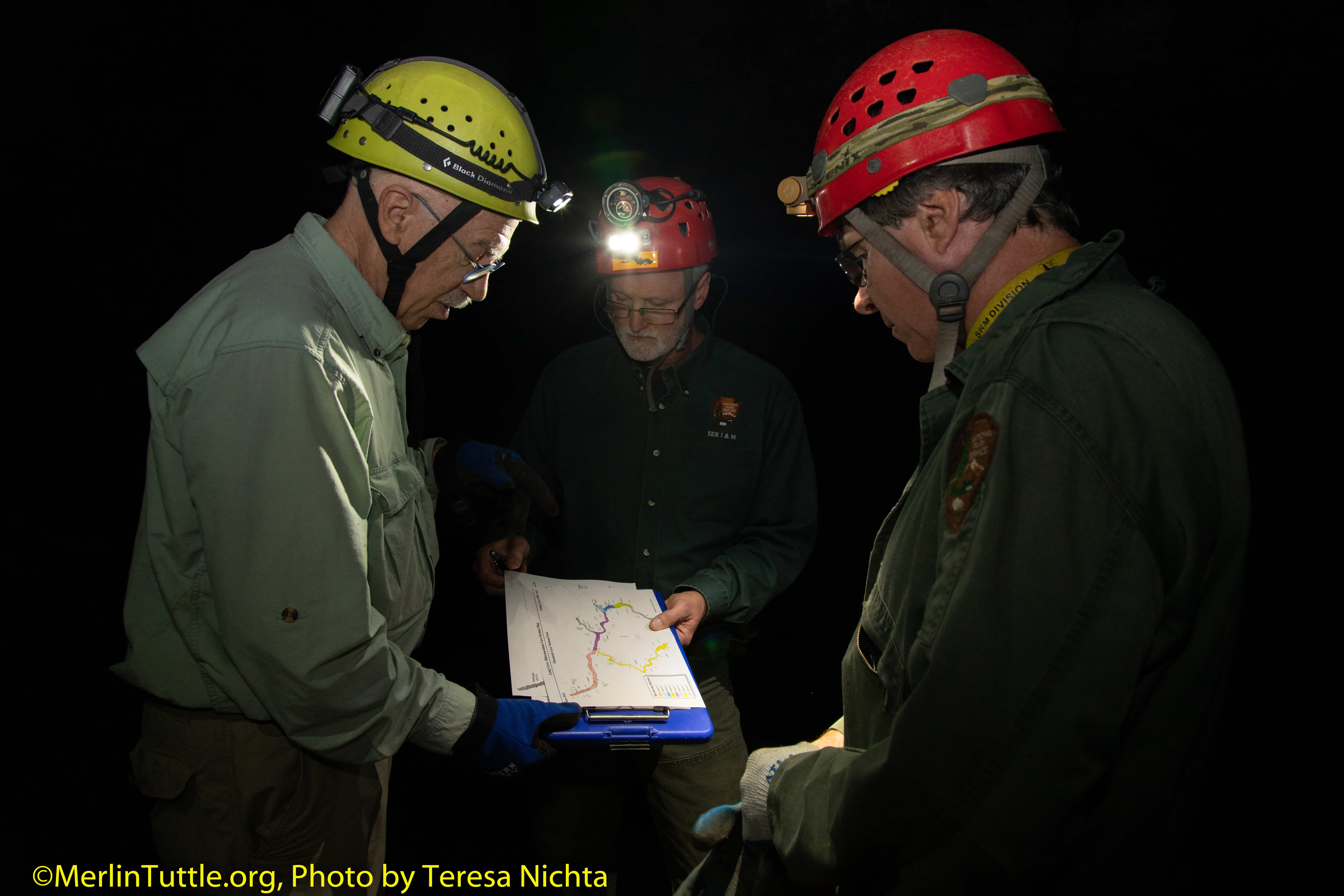

Janet Tyburec and John Chenger invited me and Teresa Nichta to assist with their bat conservation and management workshop on August 26 and 27, in collaboration with the Mammoth Cave National Park. I spent the first morning explaining the special needs of cave-dwelling bats, how to recognize evidence of past use, and how to restore and protect key sites. The next day Mammoth Cave National Park Service resource managers led us on field trips to discuss bat conservation options and successes in park caves. These included Tim Pinion, Chief, Science and Resources Management, Rick Olson, now Park Ecologist, and Rick Toomey III, Cave Resource Management Specialist and Research Coordinator, and Steve Thomas, Monitoring Program Leader for the National Park Service’s Cumberland Piedmont Network.

Our hosts were especially enthusiastic about obvious progress resulting from our joint efforts begun nearly 20 years earlier in Long Cave. The park is monitoring both low temperature restoration and resulting bat population growth and enthusiastically reported wonderful progress there. I was particularly thrilled to learn that the 2019 survey conservatively documented a current winter population of at least 300,000 gray and Indiana myotis, mostly the former, in addition to other species not surveyed. Having subsequently gone on to other priorities, this was a very pleasant surprise for me!

Prior to leaving the area John, Janet, Teresa and I also visited James and Coach Caves, owned and protected by the Rockcastle Shooting Center just outside the park. I had conducted research there in the late 1960s and early 1970s and had convinced the former owner to end commercial tours that were causing precipitous decline of hibernating bats. Subsequent efforts reopened air flow and provided a bat-friendly gate at Coach Cave, as well as removal of an airflow-restricting door and provision of a bat-friendly gate at James Cave. However, at James someone had failed to understand the importance of removing not just the door, but also the substantial rock and concrete wall, which was left in place behind the new gate. Apparently, this omission prevented adequate restoration of cooling air flow needed for hibernation.

Coach Cave had formerly sheltered more than 100,000 hibernating Indiana myotis, down to 100 or fewer before protection. James had been home to 200,000 or more hibernating gray myotis but they had declined to only about half of former numbers.

These larger gray myotis moved to Coach Cave’s apparently better restored hibernation temperatures, likely preventing re-population by Indiana myotis. Unfortunately, though both caves were surveyed at two-year intervals for bat numbers over the past 20 years, roost temperatures weren’t compared, and the remaining rock wall at James Cave remained.

During our visit, I noticed the remaining wall, and we advised a year of simultaneous data logger recordings, in and outside of both caves, followed by removal of the restrictive wall at James Cave. I am hopeful that a clear lowering of roost area temperature in James Cave, followed by a gradual return of gray myotis, will open a brighter future for still declining Indiana myotis. Up to a decade or more may be required to test my hypothesis but resulting knowledge may contribute greatly to the long-term recovery of endangered Indiana myotis.

Hibernation temperature restoration can be vital to bat recovery, and as seen in Long and James Caves, can have major impact. It is my strong suspicion that loss of traditionally suitable hibernation temperatures has greatly increased American bats’ vulnerability to the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome. Bats already stressed by inappropriate roost temperatures are likely the first to succumb, and those where suitable temperatures can be restored should be the first to recover.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Can we afford to lose bats? A recent study by Eyal Frank of the University of Chicago reveals that the dramatic decline in U.S. bat

Bats are among the most fascinating yet misunderstood creatures in the natural world, and for many conservationists, a single experience can ignite a lifelong passion

Many bat conservationists know that Kasanka National Park in Zambia is an exceptional place for bats, but it is also the place that sparked my

The Kasanka Trust is a non-profit charitable institution, which secures the future of biodiversity in Kasanka National Park in Zambia. They welcome internships for students

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.