Challenging torrential rains countered by cooperative bats in Costa Rica

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Meticulous preparations were required for the climb and subsequent month-long collecting atop Cerro Duida. This extra large tepui, a table-top mountain, abruptly rises to a plateau area covering more than 420 square miles, at elevations ranging from 4,600 to nearly 7,800 feet.

The mountain had previously been explored only on the south side. An American Museum of Natural History botanical expedition had scaled that side in 1928-1929, reporting dramatic changes in vegetation. Merlin’s team would scale the north side, providing the first glimpse of animal life. He hoped that a month would be sufficient for his seven-man team to sample the mountain’s unique ecosystems.

Villagers assembled to see the men off on the morning of January 11, 1967. Merlin and Fred’s wives, Claudette and Virginia, remained at base camp, supervising local village collectors. The couples communicated via letters sent back-and-forth by couriers, along with fresh plantains and an occasional can of peas. The expedition, lead by Merlin Tuttle, included Fred Harder and five Maquiritare men, all eagerly anticipating this grand adventure on a climb none had previously made.

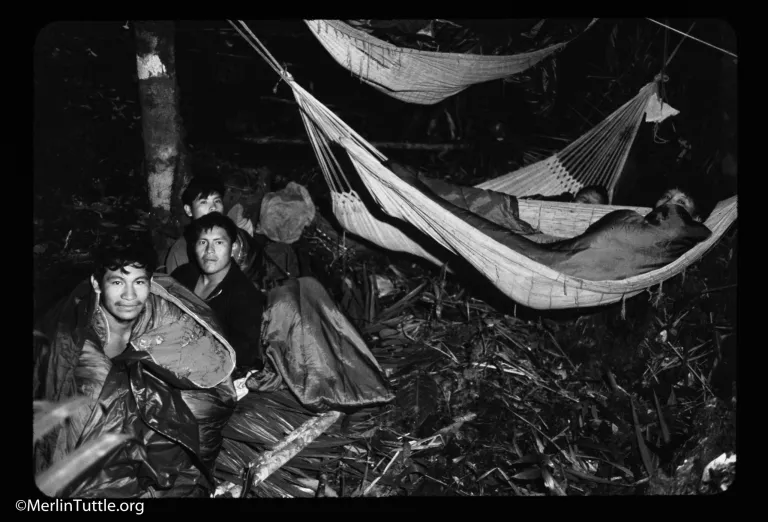

The Maquiritare, accompanied by their dogs, were incredibly vigorous with unlimited stamina. Most hauled fiberglass cases, each loaded with 55 pounds of supplies, except for Gonzales, a virtual iron man who enjoyed demonstrating his superior strength. He insisted on carrying an 80-pound pack.

Packs were suspended from foreheads or chests using wide straps made from tree bark (Seen in the top photo). They contained everything necessary for specimen collecting and processing, along with camp supplies and food. Merlin and Fred were the only ones outfitted with traditional backpacks.

Crossing a small savannah and wading a stream, they soon began hacking their way with machetes through dense vegetation, beginning a steep, trailless climb. Despite their heavy packs, the men would climb more than 2,000 feet of nearly vertical terrain, often relying on large vines and ledges to haul themselves up.

Midway, they had stopped to enjoy the spectacle of a nearly thousand-foot waterfall, when the dogs suddenly charged into the forest. They had scented a giant anteater, the first specimen collected.

Returning to the climb, one of the Maquiritare spotted an almost invisible but deadly snake, an eight-foot long bushmaster. This snake’s venom has relatively low toxicity. However, using three-quarter-inch fangs, it can inject so much venom that bites are nearly always fatal.

The Maquiritare quickly retreated some 50 feet away. Since this was a mammal-collecting expedition, Merlin hadn’t intended to collect snakes, but he couldn’t resist having a closer look. They were astonished when Tuttle announced that he wanted to capture it alive. He knew that the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Caracas desperately needed one for production of antivenom. He hoped to send the snake downriver to Esmeralda from where it could be flown to Caracas.

Backing up to a safe distance, Merlin prepared for the unexpected capture. He quickly emptied clothes from a heavy-duty plastic bag in his pack and removed his shoelaces. In the meantime, he asked one of the Maquiritare to cut a sturdy six-foot pole from a nearby sapling. He tied the shoelaces together, formed a slipknot loop at one end, and securely fastened the shoelaces to his pole.

He then returned and slowly approached the coiled snake. Meanwhile, his Maquiritare helpers begged him to stop before he got bit, warning him it was sure death.

Heart pounding, he very cautiously slipped the noose over the snake’s head and tightened it. The powerful snake immediately attempted to escape but was gradually dragged from its hiding place. Merlin had no option but to grasp it behind the neck.

Meanwhile, the snake frantically attempted to imbed its long fangs in Merlin’s fingers and coiled its powerful body around anything within reach in an attempt to free itself. He was terrified to see its fangs reaching within less than half an inch of his hand. This was something he hadn’t anticipated. Nor did it get any easier when he had to release one hand to open the plastic bag and begin stuffing the snake’s writhing coils inside.

Finally, he had to pin the snake’s head to the ground with his boot while releasing his hand from its neck and quickly tying off the top of the bag. He was never again tempted to try such a feat!

That accomplished, he found that none of his helpers wanted to risk carrying the bagged snake back to base camp. He ended up having to pay nearly a month’s wages to induce one of the men to carry it back suspended from the end of a 6-foot pole.

Imagine what Claudette felt, when she received the bagged snake with instructions on how to contain it and keep it alive until they returned!

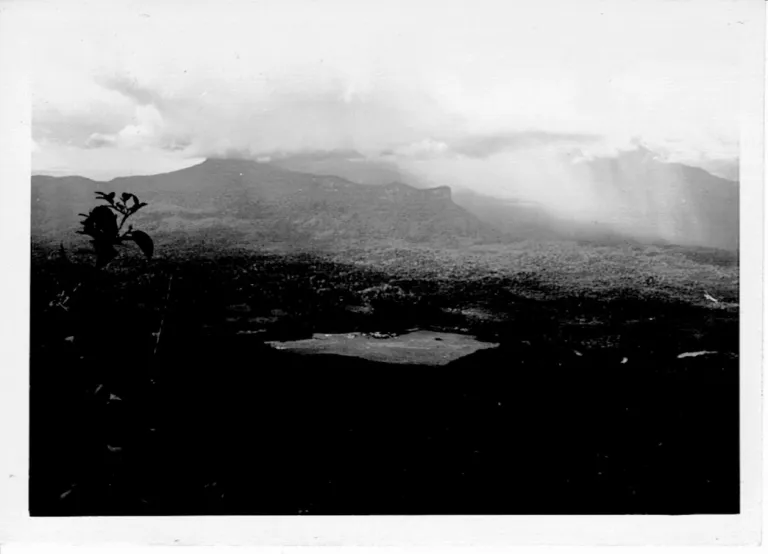

The group resumed the climb. And several hours later, they crested the summit not far from a waterfall. The spectacle was breathtaking. Approximately 90% of the plants were unique (endemic) at the genus level from any encountered below. One had the impression of having traveled far, far away from Belén.

Though the Maquiritare didn’t seem to be much worse for the wear, Merlin and Fred were exhausted. Added to the suffering, Fred had slipped and grabbed the spiny trunk of an astrocaria palm, the equivalent of grabbing a porcupine.

They quickly cleared an area for the first camp less than 100 feet from a gorgeous view of their base camp in Belén some 2,000 feet below. Several miles beyond Belén, they could also view the similarly spectacular cliffs of Cerro Duida’s sister tepui, Cerro Huachamacare.

They didn’t just encounter unique vegetation; they were now faced with a very different cloud-forest climate. With little warning, a single passing cloud could deluge their camp. They had to take turns drying their bedding and clothing in the sun, ready to cover them beneath a tarp at a moment’s notice. Fortunately, Merlin had anticipated much cooler nights, so had provided the team with sleeping bags.

The Tuttles and Harders had a system of signaling with flashlights so they would know if there were problems or if all was well. The group spent three weeks at this camp, and the flashlight signals worked for a while. Eventually, other villagers joined in the fun, and it became an unreliable form of communication. The couples gave up on light signals and sent letters back and forth with couriers who went down the mountain to base camp for plantains and incidentals.

Virginia devised a clever method of communicating with Fred, by writing letters to him that he could quickly and efficiently respond to, by checking off boxes of possible answers to questions she had: Dear, a checkbox for wife, honey, or sweetheart. We have gotten, and a checkbox for lots, few, or no animals. We are, and either wet or dry. Once completed, the letter was returned to her by the courier.

Collecting also proved challenging. They could hardly force their way through dense forests to set nets or traps on the plateau. Merlin even climbed down the cliff face to set traps along narrow, vegetation-covered ledges up to 50 feet below the top. However, the only rats captured there were also common on the plateau.

Similarly, the only good site available where bats could be netted was on a narrow ridge extending out from the cliff face some 50 feet below the top. Bats that apparently rode thermals up the cliff could be netted at this unique location, but a misstep could’ve plunged a netter into the forest more than a thousand feet below.

A total of 48 bats were netted there, belonging to four genera and five species. Surprisingly, more than half belonged to three species of nectar-feeding bats, yet the team didn’t see any flowers known to be bat-pollinated.

It was later reported that more than 20 species of tank plants (bromeliads that trap and hold water) rely on bats for pollination. Given the countless tank plants found farther inland on the plateau, Merlin now wonders if possibly these plants may have been providing a feast for otherwise lowland bats that could easily ride thermals to reach them, like similar bats appear to do in the Andes.

Despite all the hard work to build their first camp, they captured a total of 155 mammals there. However, the team did capture one new species, later named the Eldorado broad-nosed bat (Platyrrhinus aurarius) by Dr. Handley. The next camp would prove more productive of varied species.

At the end of the first week, Merlin sent two of their Maquiritare helpers out with machetes to clear a trail and scout for new habitats for a second campsite. They reported a wide variety of habitats. In some areas, a misty rain fell almost continuously, and everything was covered in several inches of moss and lichens, favorable habitat for poison dart frogs. In others, three- to six-foot-tall tank plants dominated.

A site with taller forest and less rain, some 10 miles farther inland, was finally chosen for the second camp. Initially, the trail followed just above the cliff face where there were spectacular views and less vegetation. Eventually they had to turn inland. Merlin recalls that it took two of his men about a week to machete through the dense vegetation inland to create a trail for the rest of the team to follow.

As the trail began to traverse the undulating plateau, unstable ground often felt like walking on jelly. Everything quivered under foot. Mats of dense moss and roots often hid cavities beneath, making hiking treacherous. The trail repeatedly crossed erosion crevasses, some of which were sheer drops of 10 or more feet to subterranean streams, heard but not seen. The men repeatedly broke through. It’s a wonder they escaped with no more than bruises.

Furthermore, where the trail passed through areas of dense tank plants, the going was made even more miserable as water spilled from the plants onto the hikers. Tank plants, aptly named for their tendency to trap and hold large quantities of rainwater, would dump it on anyone attempting to use the narrow trail.

Wet, bruised, and exhausted, much work remained to be done before a new camp could be established. Seemingly endless trees, some large, had to be cleared to let the sun in. Without direct sun, mold would quickly consume the camp, and specimens could not be dried for preservation.

Tree clearing was tricky and dangerous, but Gonzales was an expert. He would cut a dozen or more, none of which would initially fall because they were held together by vines. He had to plan carefully, leaving a larger tree near the middle for the final cut. The real challenge was to fell the largest tree, without being trapped when the rest all fell at once.

Felled trees couldn’t just be left in jumbled piles. A massive tangle of leaves, vines, and branches had to be cleared. Then they had to be cut into pieces used to make floors, benches, and work tables.

The site was located less than 100 feet from one of the area’s rare surface springs. Water was redirected from the spring to the camp via an open flue duct made from lengthy pieces of bark. Worktables, sleeping areas, and the kitchen were shielded from rain, using light-weight tarps tied firmly over cords between trees.

Even eating was a challenge. Merlin and Fred were vegetarians and survived on little more than a mixture of oatmeal, Carnation Instant Breakfast, and occasional plantains delivered by the couriers. (This was long before dehydrated meals for backpackers became widely available). The Maquiritare sometimes supplemented their diet of mostly manioc and cassava (a staple food of the South American frontier) with a plantain, mixed with monkey meat and local wild honey. These were mixed into a rather strange stew. They offered to share, but Merlin and Fred had no appetite for monkey! (The monkey skulls and skins became part of the Smithsonian collection.)

Rodent collecting went especially well at the second camp, far better than at the first where only two species were collected. A variety of tall forest and open tank plant habitats yielded 60 rodents of five genera and nine species, including a new species of climbing mouse.

Good bat netting sites were nearly impossible to find. Yet, by climbing slender trees that protruded above the tank plants, the team managed to precariously spread 42-foot mist nets tied with cords of varying length to the trees instead of poles. Removal of captured bats required at least one team member to climb a tree, release one end of the net, and lower it to a partner waiting on the ground. And, as if that weren’t enough, they seemed to have a knack for catching unwanted owls!

Nevertheless, in the two weeks at Camp 2, the team managed to capture 60 bats of four genera and five species, all nectar- or fruit-eaters. Again, they were unable to discover which plants the bats were servicing.

Insect-eaters were conspicuous by their absence. Nets must be especially well set to fool them. Failure to catch such bats likely resulted from sagging nets being easier for these generally smaller, more maneuverable species to detect and avoid.

The return to base camp covered some 15 miles of extraordinarily rugged hiking in a single day. An overnight camp in increasingly frequent rain was simply not feasible. Merlin and one of the Maquiritare men had returned a week earlier to begin preparation for the expedition’s departure.

A week later, exhausted, but nearly back to base camp, the rest of the team encountered a big surprise when about an hour away. Jaguars normally attempt to avoid humans unless cornered. Nevertheless, they met one that apparently was exceptionally hungry or in a very bad mood. When the porters spotted it brazenly blocking the trail ahead, they gathered in a group, facing out, machetes in hand. As they waved and hollered, the big cat simply took a cautious step forward. They were unarmed except for a .22 pistol loaded with dust shot for collecting, and even it was buried in a pack. While one man frantically unpacked it, the others stood guard brandishing their machetes. When several shots were fired into the air, the cat simply disappeared into the surrounding vegetation. Half an hour later the men warily resumed their return.

In late February 1967, the crew packed and headed back down to the New Tribes Mission headquarters in Tamatama to replenish supplies and deliver some 1,800 carefully packed specimens of approximately 100 species (the combined total for Belén and Cerro Duida) for shipment to the Smithsonian.

The expedition got back in their dugout canoes, motored down the Rio Cunacunuma to the Orinoco, and eventually on to the Rio Mavaca which took them to Boca Mavaca, their next destination. This was Yanomamö land!

In his 1969 book Yanomamö: The Fierce People, the anthropologist, Napoleon Chagnon, in the footnote on page 1 writes:

“On my second trip, January through March 1967, I spent two months among Brazilian Yanomamö and one more month with the Venezuelan Yanomamö.”

Napolean A. Chagnon, Anthropologist

This is when the paths of Tuttle and Chagnon crossed.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Bats can use sounds in many complex ways. They can sing and even have different dialects… When imagining a bat, the first thoughts that come

It was a long road to Austin, Texas. More than five years after my first introduction to Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation as a teenager, I packed

TEDx Talks recently released the video of Merlin Tuttle’s fascinating presentation about bats at TEDxUTAustin’s seventh annual conference, held on March 23rd. During his presentation,

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.