Challenging torrential rains countered by cooperative bats in Costa Rica

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

While working at his new camp at Boca Mavaca, Merlin noticed two men, who were conspicuous by their extraordinary curiosity. When he questioned Cecil Neese, his local host, he learned they were visiting from a distant Shamatari village. Cecil explained that he and anthropologist, Napoleon Chagnon, (see Blog 4, Yanomamö and Boca Mavaca) had visited their village a year earlier, staying just one night. That had been the village’s first contact from the outside world. When Merlin learned of this, he was immediately overwhelmed with curiosity to see for himself.

He asked his Yanomamö and Maquiritare guides, Ramón and Gonzales, to accompany him. (Ramón was a name given by missionaries, not his actual Yanomamö name.) However, both refused. Merlin recalls, “My guys said, No way, they didn’t want anything to do with such a trip. They knew far better than me how dangerous it was. But I finally persuaded them by offering each a couple of months’ pay for a several day trip.”

The trip was tricky from the beginning. They had to climb 15 feet of vertical vines from the Mavaca River just to reach the trail head. It had rained all night the night before, and the trail was wet and slippery. While Merlin carried a 45-pound pack (including his 16-mm Bolex movie camera, a tripod and film), their Shamatari guides, unencumbered, kept a fast pace, just short of a trot. Merlin’s pedometer indicated 5-miles per hour. The jungle was like a huge steam bath. They had to wade flooding streams every few minutes, keeping them soaked. Merlin’s glasses were continuously fogged, with so much sweat running down them, he could barely see. His wet pants rubbed his knees raw. Large blisters on his heels broke and hurt like hell.

By the time they stopped for the night at about 5 PM, they had covered 20 miles. Merlin was so exhausted he felt like he’d die if he couldn’t get to food and a hammock quickly. Only then did he discover the reason for the day’s blistering pace.

As Gonzales, Ramón, and Merlin began unpacking their hammocks beside a beautiful, crystal-clear stream, they noticed the two Shamatari were preparing to spend the night by themselves well away from them. Gonzales immediately became suspicious, so he and Ramón went over to have a chat with them. They admitted fearing enemy attack. Though reluctantly invited, Merlin, Gonzales, and Ramón quickly joined them.

The problems just seemed to cascade. When Merlin began preparing his evening meal, he discovered that all but Gonzales were assuming he would feed them. Yet, due to weight limitations, he had barely brought enough food for himself. He finally boiled about a gallon of water over a small fire to which he added a cup of powdered milk, a cup and a half of oats, and a package of dehydrated tomato soup intended to make a quart. Gonzales added a couple handfuls of his dried manioc (made from ground up yuca). For guys who hadn’t eaten since their morning departure, it ended up a rather tasty concoction!

At midnight, they were hit with heavy rain, and Merlin spent the remainder of the night soaked and shivering. His hammock was longer than those of his men, so didn’t fit beneath the temporary shelter they had constructed from vines and overlapping palm leaves.

They were up at the crack of dawn and left in great haste without breakfast, rushing to evade potential enemy attack. They again averaged five miles per hour, arriving at the village by mid-day. As they approached, the Shamatari men made bird calls, apparently to alert the village that they weren’t the enemy.

Villagers enthusiastically welcomed Merlin and his companions and offered places to hang their hammocks beneath one of the village’s 13 shabonos (lean-to shelters). To his surprise, Merlin had barely unloaded his gear when they began offering to show him local bats. They seemed a bit puzzled to find him more interested in them than the bats he was rumored to love.

The curiosity went both ways. They were also extremely curious about Merlin and nearly everything he owned. They were endlessly fascinated with extendable tripod legs, with the moving hands and sounds from Merlin’s watch, and with his ability to cut an apparent rock (a tin can) open to obtain food.

When they asked to borrow essential items, such as Merlin’s glasses, he had to be especially careful that they weren’t mistaken to be gifts. Without Cecil, he had to speak Spanish to his Maquiritare interpreter, Gonzales, who translated into Yanomamö for Ramón who assisted with the Shamatari dialect. There was ample opportunity for error!

That evening, Gonzales explained to Merlin what he should do if there was a night-time raid. He had confirmed that a raid was believed to be imminent. He told Merlin that he should simply fall to the ground and play dead, because there would be no hope of knowing who was friend versus enemy in the ensuing melee.

At sundown, three men started taking ebene (a powdered hallucinogen obtained from the bark of a local tree) blown up each other’s noses with a wooden pipe till they were high enough to communicate with the hekura (spirits). They then ran around the village shooting arrows at hallucinated hekura. Merlin lay perfectly still in his hammock, listening as their arrows struck the thatch. He couldn’t help wondering if one of the hallucinating guys was going to mistake him for a spirit and shoot him. Imagining how it would feel, he was plenty scared.

Just as the shooting had finally started to die down a bit, and Merlin thought he might survive, he reported:

“All hell broke loose, people–screaming and hollering! It’s difficult to even imagine the sounds that can come out of terrified aborigines. As instructed, I baled out of my hammock and played dead. People were tripping over me, as I was trying hard to pretend, believing people were being shot and dying. It seemed like forever, but it was probably just a few minutes.

Finally, it got very quiet. Then I heard approaching footsteps. Was this enemy warriors checking to make sure there were no survivors? I held my breath and tried to look as dead as possible. Suddenly, I heard Gonzales’ unmistakable laughter. It had all been a false alarm, and I was the only casualty! Ramón and Gonzales found it very funny.”

Merlin Tuttle

Apparently, a guy had gone out to relieve himself, and when somebody saw, but didn’t recognize him, an alarm had been sounded.

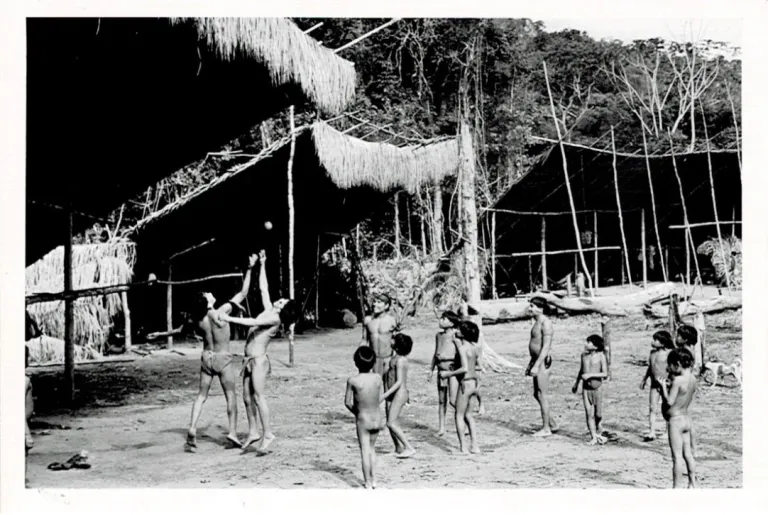

Life with the Shamatari was a continuous adventure. To Merlin, their way of life, and everything they did, was fascinating. In just his first two days of what ended up being a week, he was able to film a wide variety of simple, but impressively sophisticated, approaches to survival in the rain forest.

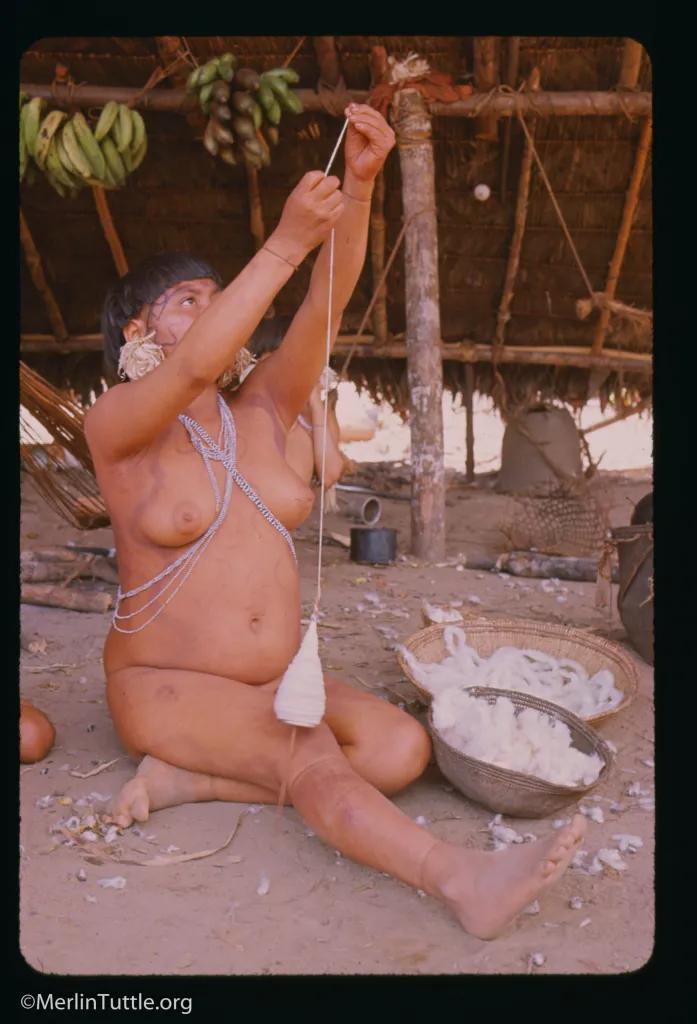

They used vines to weave baskets and sturdy hammocks, tree bark to make harnesses for carrying heavy loads, gourds for eating utensils, and animal teeth for knives. They grew their own cotton, and the women were extremely clever at using small, pierced stones, combined with hardwood sticks, to quickly spin thread (a drop spindle).

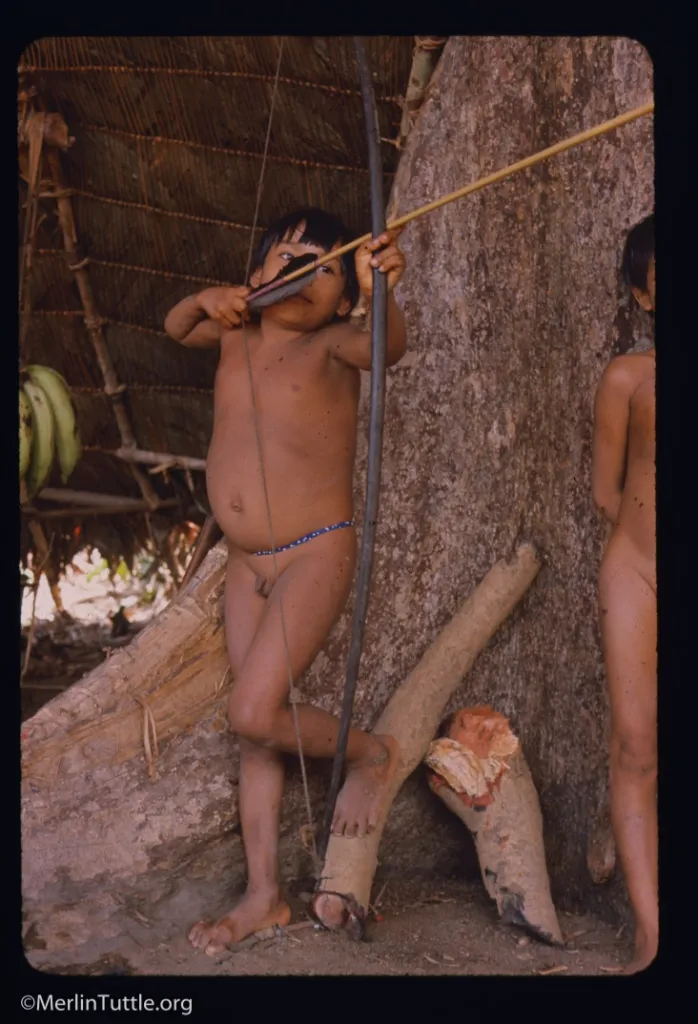

Powerful bows were made from the hardwood of certain palms. The seven-foot arrows required extra mass to minimize deflection caused by dense forest foliage. Arrow heads were interchangeable, some large and flat, others about the diameter of a pencil. The latter were used for hunting monkeys high up in the forest canopy and for killing enemy humans. These heads were made of hardwood, each with three circular cuts at about two-inch intervals. Coated with curare from jungle vines, they would shatter into the equivalent of shrapnel on entry into a target, ensuring quick paralysis and death.

Merlin was especially intrigued with fire-making. Shamatari men could quickly start a fire using a termite nest as tinder.

First, someone had to climb vines some 20 feet up to reach and harvest a termite nest. As the half-inch-long insects emerged, they were knocked loose, falling onto large leaves in which they would be rolled up and cooked for a tasty meal. Meanwhile, the nearly rock-hard nest would be broken into several pieces and carried back to the village as kindling for fire-making. Intuitively, these would hardly seem appropriate for such a purpose. Yet, they were dry inside and highly flameable.

Merlin was invited to eat guama fruit with a Shamatari family. They break open green bean-like pods some 18 inches long to consume a thin layer of sweet pulp surrounding marble-sized black seeds. People were quite generous in offering to share their food, though some was just too strange to try, for example roast grub and boiled monkey eyes.

Nevertheless, Merlin soon learned a hard lesson. Return generosity with his unique food was expected, soon forcing him to eat just one meal a day. The Shamatari were always extremely curious to see what new thing he’d eat next. When he used a pocket knife can-opener to open a can of peas, there were many oohs and aahs. How could one possibly get food from a rock? So many people crowded around that he could scarcely move. Then, everyone insisted on trying just one pea, a seemingly reasonable request. But, with 89 people in the village, only a few peas remained for Merlin!

Pijiguao fruit was a village favorite. It came in bunches, gathered from spiny palm trees. The fruits were shaped like miniature coconuts and brightly colored orange or yellow. However, it had to be boiled in a kettle before being eaten. It was peeled like a banana and resembled a sweet potato.

Gonzales explained that the kettle, single ax, and two machettes seen, had been obtained through trade with the Yanomomo at Boca Mavaca and were extremely prized. Items as simple as pairing knives and needles seemed to have outrageous value. But one of Merlin’s most sought after trade items was his hard candy.

Running low on food, he traded two pieces of candy for 15 ripe bananas. The novel candy was apparently a huge hit. Almost immediately, villagers were bringing dozens of bananas to trade. They were disappointed, but laughed when Gonzales and Ramon explained that Merlin couldn’t possibly eat so many.

After lunch, the said-to-be head man of the village got a two-foot-long tube and some powder called ebene, and a younger man began blowing the powder through the tube into the older man’s nose. When Merlin first saw them preparing he had, through Gonzales and Ramón, asked permission to film and believed it had been granted.

The drug must have been potent. Soon the man was chanting, screaming, howling, flailing his arms, obviously very high. Then he began attempting to chase the hekura (evil spirits he believed to be making a woman sick) from the village.

Just as he was spectacularly high, and Merlin was thrilled with the footage he was getting, the man suddenly attacked. Merlin recorded the incident in his diary.

“Without any warning, the man sprang to his feet, grabbed an ax and came after me. He got within swinging distance in a flash and raised it high. I grabbed my camera in one hand and grabbed for the ax handle with the other, standing my ground. His muscles tensed, and just as I was sure it was going to come down hard, he stopped as though surprised and went back to where he had been.”

Merlin Tuttle, account from his diary

Gonzales and Ramón quickly intervened, informing Merlin that the whole village was angry and had ordered them to leave immediately. Gonzales clearly feared for their safety and he and Ramon urged a hasty departure.

Merlin stalled for time as he made a show of packing, then removed a very nice hunting knife from his pack and persuaded his very reluctant assistants to accompany him to present it to the offended man as a gift.

The man was clearly pleased, apologized for attacking Merlin, and invited Merlin to share some guama fruit with him and his family. Merlin of course also promised never again to interfere with men chasing hekura. Most importantly the offended man became Merlin’s invaluable friend and even invited him to join his village.

That evening, when Merlin turned on his headlamp to write in his diary, several boys joined him to observe. Soon they were distracted by the arrival of June beetles attracted to the light. They’d quickly grab them and pop them into their mouths alive, eating them like candy.

A little later nearly the entire village became involved in a noisy dispute. They formed two lines, screaming apparent insults at each other. When Merlin questioned Gonzales and Ramón, they explained that the dispute began earlier in the afternoon when a newly married young lady asked another woman to share her tobacco. Both men and women often inserted a rolled up strip of tobacco leaf inside their lower lip.

The other woman refused to share, which greatly offended the young lady. Later, she reported the incident to her husband who promptly went over and chopped the other woman’s hammock in two, infuriating her family. His bride became angry at him for overreacting and refused to prepare his evening meal. When he got angry, she took her own hammock and fled to her father’s shabono, announcing she didn’t want to be his wife anymore. Relatives took sides, and even non-relatives got drawn in.

It sounded like a fight was imminent, but Ramón correctly predicted it wasn’t serious. Someone could get hurt, but in the morning her father and husband would settle the matter, and all would be forgotten. The girl wouldn’t have much say in the matter.

Soon, the men and boys began trotting back and forth in front of one of the shabonos, holding hands and singing in an apparent show of male solidarity.

Some disputes didn’t end so amicably. One day, shrill screaming drew Merlin’s attention to a nearby shabono just in time to see an angry woman brand another with a stick from a cooking fire. The still glowing tip was thrust into another woman’s abdomen, leaving an ugly burn. Given the number of suspicious scars, the practice appeared common.

Men resolved their most intense disputes in chest beatings or head bashing with eight-foot hardwood poles. Most of such duels weren’t lethal, and none occurred during Merlin’s brief stay. Nevertheless, scars from past head bashings were proudly displayed. Both Shamatari and Yanomamo men wore the tops of their heads shaved to show proof of past engagements.

Another strange male behavior involved tying a cotton string around the foreskin of their penis, holding it in an upright position by extending the string around the waist just above the hips. Merlin never saw a string come untied, but wondered how a man would react. Would he immediately attempt to hide like a westerner who’d lost his clothes?

Women commonly engaged in what behaviorists would call social grooming. They would carefully run their fingers through each other’s hair searching for lice. When one was found, it would be carefully removed and eaten–a sure way of ensuring it wouldn’t return!

On the subject of hair, I noticed in all of Dr. Tuttle’s photographs and videos, both the Yanomamo and Shamatari men, women, and children had short bowl-shaped haircuts. Without tools like scissors, I wondered how they cut their hair and why the uniformity. I asked him about it, but he never witnessed them cutting hair.

Following several days of relative calm, enemy warriors were detected, said to be waiting to ambush any villagers who ventured forth.

Women wouldn’t even venture 100 feet outside from the ring of shabonos to obtain water without a contingent of warriors to guard them. Merlin, Gonzales, and Ramón had to drink untreated water collected from the village bathing pond. (Merlin’s small bottle of Chorox for water treatment had been lost in a spill.) Furthermore, reluctance to go hunting or to the garden, meant an imminent food shortage.

The Shamatari had, on balance, been quite kind and generous, but as potentially severe hunger developed, Merlin and his two companions realized they’d be first to suffer.

Ramón advised that they attempt to leave as soon as possible. He engaged in a long consultation with the head man and returned with a risky, but potentially only-hope idea. He’d been informed of a secret, but longer trail through rugged terrain, one where the enemy might not be watching as closely.

Napolean had warned Merlin not to take guns. The Shamatari would want them and could end up taking them by force. So he, Gonzales, and Ramon now faced the challenge of sneaking past the enemy unarmed.

Merlin recalls:

“We left at 11:15, the time of morning when the enemy was speculated to be least alert. I carried a 38-pound pack, mostly containing my movie and still cameras, film, and a small bag of hard candy, our only food for the day. Ramón and Gonzales each carried similar weights, our hammocks and mosquito nets, clothing, and prized possessions I’d traded for.

Ramón led the way, often having to read broken twigs and other faint trail signs. Gonzales followed while I brought up the rear, acutely aware that the one in that position would be the first shot in an ambush.

We averaged a near run, covering approximately six miles an hour for the first 20 miles. I was so exhausted that when we’d approach the top of a hill, I’d lose my vision, and things would go hazy. I’d fear passing out. Then as we’d go over the top, and head down the far side, I’d get my vision back, and I’d swear to myself that I would keep going at least till the next hill, always spurred on by vivid imagination of feeling the first arrow in my back.

I just went from hill-to-hill like that. We’d come to streams where we would wade or swing on vines to avoid leaving tracks, anything to slow pursuit. Just as I felt I couldn’t take another step, we arrived at the base of an at least 500-foot-tall hill. I tried, but finally collapsed. My pedometer indicated we’d covered 25 miles. Both Ramón and Gonzales begged me to get up and keep going. They insisted that if we stopped too long we wouldn’t be able to continue.

I hadn’t realized just how frightened my companions were. We shared my small remaining bag of hard candy. And I was finally able to stand and lurch from tree to tree, grabbing them to keep upright. Unbelievably, I finally reached the top of the hill and got a new spurt of energy going down the far side.

Facing roughly 85-degree F temperature and near 100% humidity, combined with hiking boots filled with water from streams, my feet were again blistered. My body broke out in a rash, and my hands swelled to nearly twice their normal size. I seriously wondered how much longer I could stay alive.

By the 30-mile point, we had still maintained an average pace of roughly five miles per hour. Fortunately, by that time, I could no longer feel pain. All three of us were moving like zombies.

Night fell, and we were deluged in heavy rain, barely able to see as we waded through standing water in the now very slippery trail. By 9 PM, Ramón had been claiming we were ‘Poquito cerca,’ nearly there, for more than an hour, and I feared we were lost. Then, I was encouraged to see an old shabono which I hoped indicated we were nearing my camp at Mavaca. Nevertheless, both he and Gonzales collapsed right there, lying in several inches of water, and announced they couldn’t continue.

By that time, my pedometer indicated we’d already traveled close to 40 miles, so I assumed that if we weren’t lost, we must be nearing our destination. Fearing that, if we didn’t keep going, I personally wouldn’t be able to continue the next day, I urged my amazed companions to get up and continue.

Since I could no longer see through my fogged glasses, I gave my headlamp to Gonzales and asked him to lead on the now more distinct trail. We were repeatedly stumbling and falling and nearly stepped on a large fer-de-lance, a deadly snake in the trail.

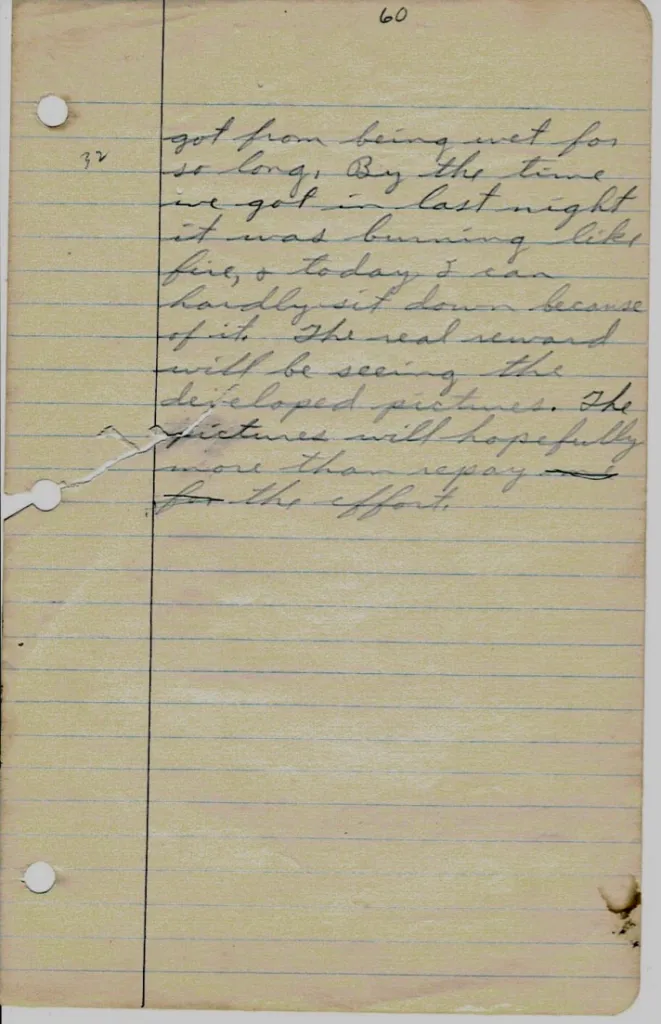

When at 10:10 PM we finally staggered into our Boca Mavaca camp, my pedometer read 45.6 miles. I was so sore from a terrible fungal rash and abused muscles that I could barely do anything without pain for several days. My companions had well earned their extra pay, and I was grateful to have survived the trip of a lifetime.

The real reward will be seeing the developed pictures. The pictures will hopefully more than repay me for the effort.”

Merlin Tuttle, from his diary

Some things never change! Merlin’s Venezuelan experience instilled a love of wildlife photography, particularly bats. His photographs of hundreds of species of bats worldwide have formed the basis of bat conservation today. You can explore the amazing world of bats at Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Bats can use sounds in many complex ways. They can sing and even have different dialects… When imagining a bat, the first thoughts that come

It was a long road to Austin, Texas. More than five years after my first introduction to Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation as a teenager, I packed

TEDx Talks recently released the video of Merlin Tuttle’s fascinating presentation about bats at TEDxUTAustin’s seventh annual conference, held on March 23rd. During his presentation,

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.