Challenging torrential rains countered by cooperative bats in Costa Rica

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

As the expedition broke camp on the Rio Mavaca, intense thunderstorms pounded the area, accompanied by torrential rain. Seemingly, almost overnight, the river rose some 20 feet. It just kept rising. By the time they reached the Casiquiare Canal, everything in sight was flooded. To find sufficient exposed land for a camp, Merlin and his field team would be forced to travel more than 100 miles up this endlessly twisting, 210-mile-long waterway, the world’s longest natural canal. It connects the Orinoco with the Rio Negro which eventually drains into the mighty Amazon. It connects the Orinoco with the Rio Negro which eventually drains into the mighty Amazon.

In 1800, the German scientist and polymath, Alexander von Humboldt, explored this part of Venezuela and charted the Casiquiare Canal, a natural waterway connecting the basins of the Amazon and the Orinoco, showing it was possible to travel by river from the Amazonas interior to the Caribbean Sea.

The lead canoe, less heavily loaded, was faster and forged ahead. The second was additionally slowed by the team’s excited pauses to view beautiful orchids, nesting ducks, and troops of 50 or more monkeys staring from treetop perches. By mid-afternoon, they’d fallen miles behind.

Suddenly the idyllic tour came to a halt with a loud thud, a whining motor, and no further progress. Obviously, they had missed seeing a submerged log. No one was too concerned. They had simply busted a shear pin. However, they soon discovered that all the spare shear pins were in the lead canoe. Worse yet, the 50-foot, heavily loaded canoe was virtually unmanageable as it floated down the canal. Fortunately, before crashing into anything, Sido and Gonzales were able to rope it to a partially submerged tree.

Now it was just a matter of waiting for the men in the lead canoe to recognize something was wrong and return to help. Nevertheless, at sundown they just waited for the others to catch up, unaware that the first canoe carried all the shear pins and that the second was stranded. They seldom needed replacements for shear pins. In those days, outboard motors were less sophisticated than those today. If the propeller struck a submerged rock or log, the pin would quickly shear, protecting it from damage.

Stranded, far from the nearest dry land, Merlin, Claudette, Fred, Virginia, Gonzalez, and Sido were forced to spend a miserable night aboard their canoe, minus the use of hammocks or protective nets. Thoroughly sprayed with Deet to ward off swarms of mosquitoes, they finally dozed off.

However, at 2 AM, Merlin suddenly realized that the fluttering wings he’d just heard weren’t a dream. Something had landed not far from his face. Guessing the source, he waved his hand, and sure enough he heard a vampire bat hastily depart.

Vampire bats are found only in Latin America. Just one of three vampire species, the notorious common vampire, (Desmodus rotundus) feeds on the blood of mammals. It is seldom encountered in undisturbed forests but has overpopulated and become a pest where forests have been replaced by defenseless livestock. An encounter on the remote Casiquiare was unexpected. Nevertheless, between mosquitoes and vampires, no one slept well that night!

For obvious reasons, the common vampire is feared, hated, and persecuted almost everywhere. No one wants to wake up to a feasting bat. In frontier areas, where the poorest, least educated people often live, it’s hard to blame them for declaring war on all bats, mistakenly killing even the most beneficial species.

The next morning the crew in the first canoe came to the rescue, and it took just minutes to replace the sheared pin and be on their way again. By that afternoon they arrived at the first exposed land suitable for a camp–just barely! The highest ground was only four to six feet above the flood line. They would later hear that they had survived the worst flooding seen in decades.

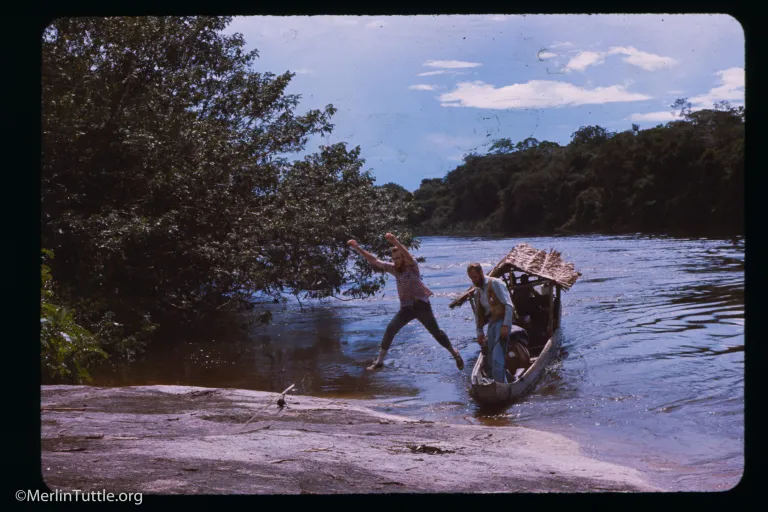

Their chosen camp site was on a low, rocky hill, known geologically as an eroded monolith. Several German families had attempted to settle the site some 15 years earlier. But all that remained were two thatched huts, and a gently sloping rock that served as a convenient landing for the heavy canoes.

The team soon discovered, with virtual certainty, why the site had been abandoned. It hosted unbelievably dense swarms of no-see-um biting gnats, so tiny they easily penetrated mosquito netting. And wherever they bit, they left tiny blood blisters. The Germans, almost certainly, had been chased out by the gnats.

Merlin’s helpers quickly observed that the worst of the pesky critters could be avoided by pitching tents for sleeping and work in shaded areas. But, whenever humans emerged to hunt or eat, they were immediately covered. Even worse, the itchy bites often developed into nasty skin lesions a half-inch or more in diameter. To treat these, team members used lava soap (soap with pumice) to scrub skin painfully raw, then dried them for half an hour in the sun.

As if threatening floods and gnats weren’t enough to drive the expedition to abandon Capibara, just a few days after its arrival, they faced an even greater threat. When a distant outboard motor was heard, team members were simply curious as to who else could be traveling to such a remote destination. Then Gonzales ran excitedly into the work tent, exclaiming over and over, Banditos vienen! Banditos vienen! He had recognized one of the men, and in the strongest possible words, warned against permitting them to come ashore.

Fortunately, the three bandits had only a small canoe outfitted with an ancient motor, preventing a rapid approach. Nevertheless, Merlin had just a few minutes in which to organize a defense.

The team was armed with two double-barreled,16-gauge shotguns and two .22 pistols with dust shot, worthless for actual defense. Guns and ammunition were quickly distributed, and team members took defensive positions behind boulders.

Gonzales warned they’d kill everyone if given a chance. One bandit was managing the motor. The other two possessed what appeared to be an ancient rifle and a shotgun. They attempted to appear friendly, but the team trusted Gonzales explicitly.

Merlin’s instructions were that he be first to show himself and take aim. As the bandits approached, he would announce in Spanish that they were known to be bandits and would be killed if they attempted to land. Taken by surprise, their guns were still in their laps, putting them at a distinct disadvantage. But they bravely smiled and continued to pretend friendship, only slowing a bit. Merlin again warned they would be killed if their canoe touched shore, and all four armed team members rose and visually took aim. Only then, just seconds from a terrible ending, the bandits finally veered away, not to be seen again.

Why be persistent? Because it must have been obvious that the expedition carried a very substantial supply of hidden bolivars. Periodically, they had purchased plantain, bananas, and cassava from the Maquiritare and Yanomamo, not to mention hiring whole villages of men to collect. Despite excellent planning for essentials, from toilet paper and insect repellent to food staples and gasoline, Merlin had to admit that he hadn’t considered possible frontier bandits.

In Caracas, he’d hidden approximately 90,000 bolivars in false bottoms of his equipment trunks. But on the frontier the fact that he must have a large supply of hidden cash would become obvious. In retrospect. it made sense for bandits to wait till the team was more than 100 miles beyond even the reach of New Tribes missionaries, or the nearest Indigenous village to plan their attack. And without Gonzales’ experience, the team might easily have been tricked into believing the bandits friendly.

The team’s only contact with the outside world was through occasionally picking up bits and pieces of Voice of America on their transistor radio. Another memorable event was hearing of a then-reported Six-day War. They had to wait a week to hear who was involved and who had won.

Meanwhile, the collecting went surprisingly well between continuously heavy downpours. However, safe storage of specimens became increasingly difficult. Study skins had to be thoroughly dried before they could be packed in order to prevent spoilage. The problem was finally resolved by devoting one tent solely for drying. It was equipped with drying racks and heated by a kerosene burning Petromax lantern.

Hides from animals such as capybara, tapir, or deer were too large for the drying tent. They had to be treated with Borax powder and dried on the large, sloping rock used for docking canoes. Inevitably, small quantities of Borax spilled onto the rock with surprising results.

One night, as the team canoed back to camp, they noticed a large number of bats circling and dipping low over the landing area rock. Using a dim light Merlin quickly discovered a steady stream of bats dipping into a mere three-foot-wide pool created by the previous day’s rain. He was amazed to see the bats approaching in nearly perfect, airport-like formation, dipping down to drink at approximately one-second intervals. Apparently, the bats were attracted to water containing Borax spilled from drying hides during the day.

Equally surprising, when a net was quickly set over the small pool, only dwarf little fruit bats (Rhinophylla pumilio) were caught. None of the five species trapped at the tapir water hole (See Blog 2, Belen Base Camp) near Belen were found.

This raised several fascinating questions, still unanswered more than 50 years later. How did these bats so quickly discover and communicate the existence of such an apparently treasured resource, unlikely to have been previously encountered? How could Borax-contaminated water have been so uniquely important at a time when other water was available virtually everywhere? And why was only a single species attracted?

It was also at Capibara that the team learned to find disk-winged bats living in unfurling heliconia leaves. These plants had long leaves similar to those of bananas. For just a few days each, new leaves provided ideal homes for these tiny bats, so-named for their suction-cup-like adhesive disks on wrists and ankles. These unique adaptations enabled the bats to securely cling to the slick, inner surfaces of newly opening leaves.

The nearby island where these bats lived had apparently been cleared long ago by settlers and had regrown into a dense patch of up to 30-foot tall heliconia plants. Since disk-winged bats require locations with large numbers of these plants, early settlers who apparently cleared the forest, had created what eventually became ideal habitat. However, when larger trees finally regrew, the disk-winged bats would lose their homes, replaced by other species. Such is the succession of life even in a rainforest. One species’ disaster may be another’s bonanza.

The team was thrilled to pack up and motor back to Esmeralda in mid-June. They were to be picked up, along with 321 carefully packed specimens from Capibara, on June 17 for a week of much needed rest in Caracas. Following a brief rest and resupply, they would continue to San Juan de Manapiare.

Nevertheless, a big problem remained. The savannah where Merlin’s team was to be retrieved was flooded beneath 10 inches of water. Would the pilots of the massive flying boxcar dare attempt a landing? The pilots were clearly nervous, circling seemingly forever before finally touching down. But, as they had feared, the plane hydroplaned on the water, skidding into a large, nearly rock-hard termite nest. The nose landing gear was bent to the point of being questionably serviceable. Yet, following a lengthy inspection, bombarded by swarms of biting no-see-um gnats, the pilots decided that flying with questionable landing gear was preferable to being even temporarily stranded there. The return flight to Caracas was uneventful, though mechanics who inspected the landing gear on arrival were amazed that the flying boxcar was able to land safely.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Bats can use sounds in many complex ways. They can sing and even have different dialects… When imagining a bat, the first thoughts that come

It was a long road to Austin, Texas. More than five years after my first introduction to Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation as a teenager, I packed

TEDx Talks recently released the video of Merlin Tuttle’s fascinating presentation about bats at TEDxUTAustin’s seventh annual conference, held on March 23rd. During his presentation,

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.