Challenging torrential rains countered by cooperative bats in Costa Rica

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

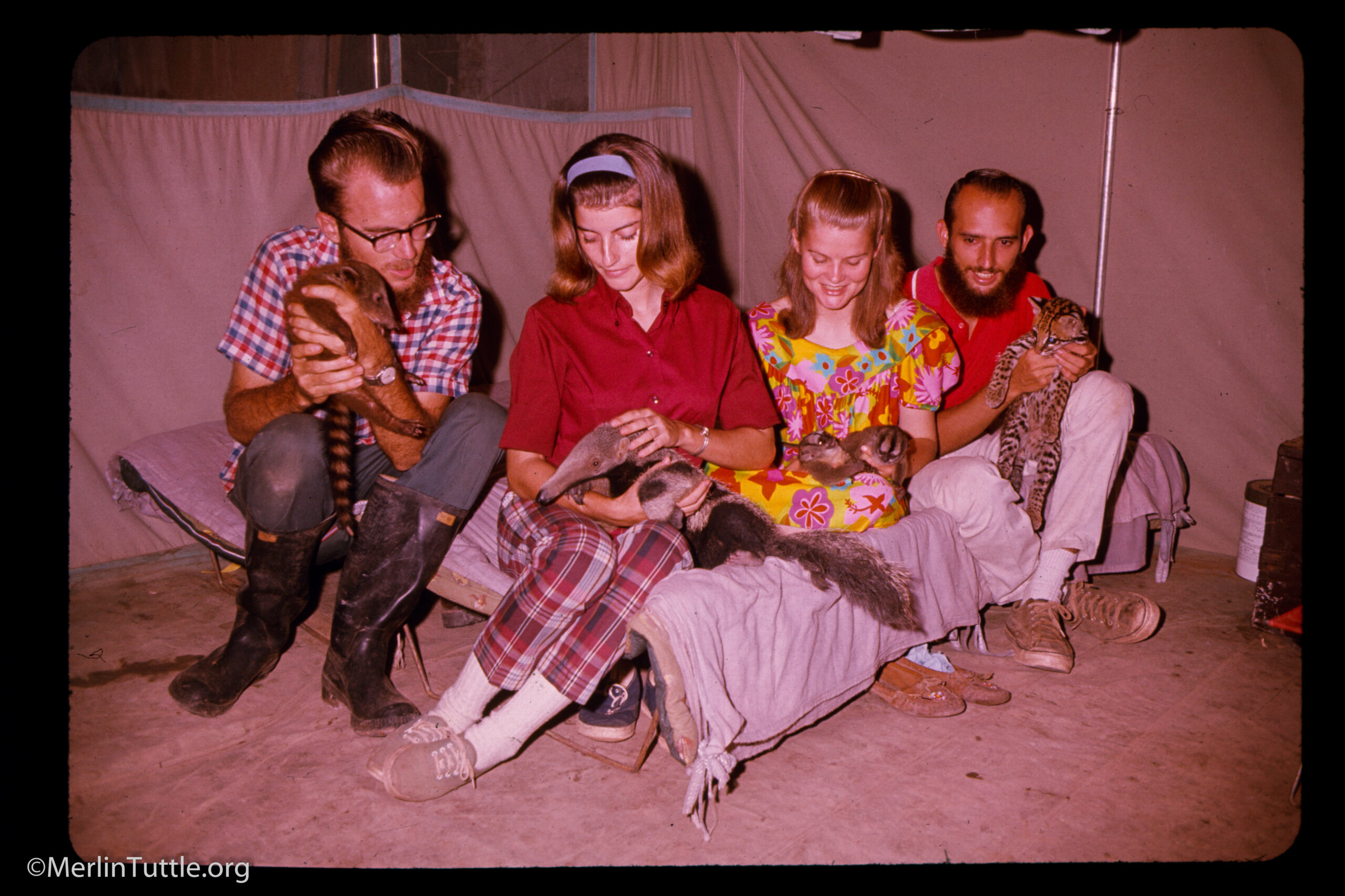

After leaving Capibara on the Casiquiari Canal where they camped from May 25 to June 15, 1967, the Tuttle expedition team had less than a week in which to ship specimens from Caracas to the Smithsonian and purchase new supplies prior to leaving for their final destination, San Juan de Manapiare. The bulk of their equipment had been sent down the Orinoco and up the Ventuari and Manapiare rivers by dugout canoes.

The airplane flight from Caracas to Puerto Ayacucho was unremarkable, as was their overnight stay in a local hotel. However, the next day’s flight between cloud enshrouded mountain peaks proved just the opposite. Forewarned of high risk, Merlin had turned to his trusted friend, locally known as Capitan Tex. Tex Palmer was an experienced bush pilot, originally from Texas. He had a colorful reputation for surviving extreme challenges. On hearing that another pilot had refused, Tex just sniggered and said, “We’ll fly at sunup before the clouds close in. Don’t be late.”

The next morning, the team arrived early. The jovial Tex was crestfallen to see the amount of luggage they had hoped to stuff into his small Cessna airplane. But they managed to load it all in quickly. Soon, they were climbing altitude to cross over some of Venezuela’s most rugged terrain. Peering into seemingly bottomless, cliff-walled canyons with majestic waterfalls was thrilling, until dense clouds suddenly obscured the view.

Tex had casually mentioned that prior to landing in a savannah adjacent to their planned San Juan de Manapiare campsite, they would have to pass between two mountain peaks, Cerro Raya and Serrania Guanay, one 8,000-feet high. He had anticipated making it through ahead of midday clouds. Unfortunately, the clouds came early.

The landing site was a grassy lowland surrounded by mountains. Coming down either early or late could be fatal. As Tex descended with zero visibility, he tried to reassure that, according to their flight speed, compass heading, and the known distance, they would soon be over the landing area. Minutes seemed like hours as the plane circled lower and lower, everyone holding their breath.

Finally, treetops burst into view less than 100 feet below, and Tex grinned broadly saying, “We’ve made it!” They were almost to the landing area, with only knee-high grass in sight. But by that time, they had become accustomed to such landings.

Upon landing, they were met by Piaroa men from the nearby New Tribes Mission outpost. They helped the team quickly load their equipment into a dugout canoe and motored down the Manapiare River to the location of their new camp. Their tents and other field gear had already been unloaded and temporarily stored in a large, thatched community shelter which would serve as the main work area, with sleeping tents pitched nearby.

The campsite was ideal, bordered on the west by 100-foot-tall rainforest, with a convenient beach on the Rio Manapiare just 75 feet to the east. The river was clear, colored a deep, rusty red due to high tannic acid content, meaning freedom from mosquitoes and biting no-see-um gnats. Compared to the swarms of biting insects at Capibara, the new camp seemed like heaven.

The gently sloping beach was ideal for bathing and swimming. As at all their camps, they swam with numerous piranha without once being bitten.

When first arriving in Venezuela city-dwellers had warned against even allowing a hand to hang over the side of a canoe for fear of losing a finger to a piranha. Like bats, they’re almost universally misunderstood. In reality, they are omnivores who feed on a wide variety of insects, crustaceans, seeds, small fish, and fins of larger fish. Some are even vegetarians. They do have razor sharp teeth and strong bites. Nevertheless, even a single bite on a human is extremely rare.

A lush savannah lay just across the river from their camp site, including large grassy areas and streams lined with moriche palms in the Ventuari Basin. The diverse habitat was ideal for collecting. The area could biologically be described as an ecotone, an area where multiple habitats met and mixed. Surrounded on three sides by mountains, this lowland area provided a rich community of mammal species at an average elevation of just 500 feet above sea-level, bordered by mountains of 3,000 to 8,000 feet.

Due to an unusual mix of habitats, collecting experience, an outstanding indigenous workforce, and logistical support from the New Tribes Missionaries, Merlin’s team was able to collect 5,632 mammals, including 79 species of bats, 14 species of rodents, 6 of marsupials, 5 of primates, 4 of edentates, 3 of artiodactyls, 1 carnivore, and 1 dolphin at this location in just 40 days. Specimens were collected from an area of a little more than a thousand square miles around San Juan.

The area supported half a dozen small villages, each including several Piaroa families and their garden clearings where they grew bananas, plantain, yuca and papayas. Humans seemed to be having minimal impact on small mammals. However, larger, edible species were already becoming scarce.

Villagers were eager for work and seemed to know exactly where to find whatever the field team needed. Merlin divided the region into 42 collecting areas, each with its habitat described in his field notes. Collectors were assigned specific areas so species’ habitats could be reliably reported.

Sido Hernandez, Merlin’s favored field assistant, played a key role in training the Piaroas in collecting and specimen preparation techniques and used a field guide to show which mammals were most needed and how much the team would pay for them. Prices per specimen collected ranged from 25 cents to 10 dollars. And each morning a sample collection of study skins of species no longer needed was displayed. Potential collectors would check to determine which animals were still needed and would work areas assigned to them and plotted on a rough map.

There was work for everyone. Some hunted or trapped. Others skinned larger animals, prepared study skins, or cleaned skeletal material. Merlin paid them by the specimen collected or prepared, or by the job performed. They were accustomed to earning only the equivalent of approximately one U.S. dollar or less per day when hired locally. But by being paid by the specimen collected or prepared, some industrious individuals earned as much as 100 dollars in a single day.

Initially, only men associated with the New Tribes Mission came to work. Throughout the Amazonas Territory, it was customary for small Protestant and Catholic missions to locate themselves on opposite sides of major rivers where they competed for converts. The New Tribes Missionaries were first to enter new areas, had the best organized supply network, and were happy to assist Merlin’s team. So they were relied on to provide invaluable communication and transport.

At San Juan, the Catholic priest apparently resented the expedition’s association with his competitors, so forbad his followers from working with the Smithsonian team. However, as word spread of the riches to be had, they too began offering their help. Exasperated, the priest lodged a complaint with the government magistrate for the area, claiming Merlin’s team to be engaged in unfair labor practices. It was true that there were no hourly or daily wages as normally required.

When an old man wearing nothing but tattered shorts showed up and sat around watching for a day, Merlin assumed him to be just another curious person and mostly ignored him. The next day, the man returned and introduced himself as the local magistrate. He presented Merlin with a rare shaman’s peccary tooth necklace (which Merlin still treasures because shamans rarely part with such items) and profusely thanked him for his generous employment practices, much to the priest’s displeasure.

Banana gardens, and even the New Tribes Mission yard, became prime collecting sites for rarely seen bats that normally hunted too high up to be captured in mist nets or traps. For example, the mission had a power generator and a single street light that attracted three species of snow-white ghost bats (Diclidurus albus, D. ingens, and D. scutatus). Without that single street light, these three species likely would have remained undiscovered. Also, the fourth ghost bat species (Diclidurus isabellus) was collected just 100 feet away, feeding low over the Rio Manapiare. This is the only record of these rarely seen species all occurring in a single location. Normal use of mist nets or traps likely would have failed to detect even one.

Merlin hopes that the time will come when more bats can be reliably identified using ultrasonic bat detectors. He suspects biologists still have much to learn about the status of bats that may be foraging high above forest canopies or living where no one has yet looked.

The smallest insect-eaters are often good at avoiding capture. For example, despite catching 79 species of bats at San Juan de Manapiare, as many as a dozen small insect-eating species likely escaped notice. Modern monofilament nets and traps do better at capturing such bats, but many still escape. High-flying free-tailed bats were abundant but found only in flood plain snags. None were caught in traps or mist nets.

The Ega long-tongued bat (Scleronycteris ega), a nectar-feeding species, was captured only once in the entire year of Amazonas Territory collecting, but likely was present at multiple locations, including in the San Juan de Manapiare area where 58 individuals of six nectar bat species were captured. Merlin can’t help but wonder if this bat might have been found to be common if only his team had been able to net 100 feet higher in the forest canopy where numerous bat-pollinated plants have since been discovered.

Four genera and seven species of free-tailed bats were found in unusually abundant and accessible snags created by extensive flooding. Despite its wide distribution across Latin America, just three brown mastiff bats (Promops nasutus) were captured, all at San Juan, burrowed into rotting wood in snags.

Ironically, tree-kills that we normally view as evidence of disaster, to be prevented whenever possible, are key to the very survival of many animals, especially bats that depend on snags for homes. Merlin points out:

To the extent that we successfully protect against fire and flooding, we can jeopardize the health of whole ecosystems.

Unfortunately, in today’s world so little habitat often remains that natural phenomena, such as fires and floods, can seriously threaten remaining populations of species that require forests. Wise protection of remnant habitats may, at times, require deliberate management to ensure a continuous supply of snags and forest openings, activities that, especially in parks, can be highly controversial.

Merlin Tuttle

Greater spear-nosed bats avoided the open area snags of the lagoons, preferring hollows in living trees. In other areas they occupied a wide variety of roosts from hollow trees to caves and even human habitations. In the San Juan area they preferred hollows in limbs and other cavities of living trees where males typically guarded harems and their young.

These two-foot wingspan bats are omnivores that eat everything from large insects and small vertebrates to fruit and nectar. They’re primary seed dispersers for monkey pot trees or sapucaia, (Lecythis pisonis), well known for the armor plated fruit contained in a cannonball-sized hard shell that protects against parrots and monkeys who are far less effective seed dispersers. When ripe, the container exudes a special odor that guides spear-nosed bats to those that are ready to eat. These large bats then pry open a previously invisible door, exposing the fruit-covered nuts which are closely related to the Brazil nut. Bats then carry one fruit-covered seed at a time away to feed elsewhere to avoid the predators waiting for them nearby.

A few bat species can occupy a wide variety of roosts and appear to prosper as human populations expand in tropical areas. The most notable example in the Amazonas Territory was the common vampire (Desmodus rotundus). This species could roost in tree hollows, caves, or human dwellings and lived in a wide variety of habitats.

More than 100 were collected in the San Juan area where the most domesticated animals had been introduced. None were captured at Capibara or on Cerro Duida where there were no humans or livestock. Just one was caught on the Rio Mavaca approximately 10 miles from the nearest humans and only four were found near the Yanomamo village at Boca Mavaca where the only domesticated animals were dogs. Few animals, other than dogs, were kept by the Maquiritari in the vicinity of Belen where 16 of these bats were captured.

Common vampires had increased dramatically in numbers where humans had introduced defenseless pigs and cattle. At San Juan, they typically were found in small groups that attracted little attention. Thus, when livestock or people were bitten, it was the insect, fruit, or nectar-feeding bats that formed the largest, easiest-to-find colonies, whose roosts were burned, sometimes killing hundreds or even thousands of beneficial bats at a time.

Local people were appreciative when Merlin explained how to distinguish the reddish, tar-like droppings of common vampires from those of bats needed for control of insect pests and for pollination and seed-dispersal. They were especially impressed when Merlin explained that some of the area’s most valued plants relied on bats for pollination, including the giant kapok tree, from which the finest dugout canoes were made.

By far the most often captured at San Juan was a species of short-tailed fruit bat (genus Carollia) that, at the time, had not yet been named; only four species were recognized. Today, there are eight.

Short-tailed fruit bats were unremarkable due to their drab appearance and ease of capture. But their ecosystem role may have been one of the most important. They are primary dispersers of so-called pioneer plants, hardy species whose seeds are adapted to survival in the hot, dry conditions found in tropical forest clearings. They are champions at dispersing the seeds of pepper (Piper), plants that are among the first to initiate forest regrowth. One short-tailed fruit bat can carry as many as 60,000 seeds to new locations in a single night.

Restoring a mature tropical forest is challenging. It requires many kinds of animals to achieve completion. Small fruit-eating bats, because they defecate seeds in flight as they fly over clearings, can contribute as much as 95% of the first pioneer plant seeds required to initiate reforestation. As these plants mature, they provide shelter that attracts birds who defecate seeds into more favorable conditions beneath perches. Even flightless animals, such as primates and rodents are eventually needed to achieve ultimate diversity.

At San Juan, more than a dozen species of fruit-eating bats were captured, each with its own seed-dispersing specialty. Some, such as the great fruit-eating bat (Artibeus lituratus) and greater spear-nosed bat (Phyllostomus hastatus), tend to carry larger seeds that don’t do well as pioneers. Nevertheless, they’re important to completion of the cycle. Many fruit-eating species also occasionally serve as important pollinators. No group of animals is more important than bats for long-distance seed dispersal or pollination, and as seen with the kapok trees of San Juan de Manapiare, many of the world’s most valuable plants rely on them.

In the small settlements around San Juan, banana gardens served as virtual magnets for nectar bats. Bananas were originally pollinated and dispersed by bats in Southeast Asia. However, when they were brought to the New World by early explorers, they immediately attracted a wide variety of nectar-feeding bats. By setting mist nets in gardens where banana plants were flowering, half a dozen species of small nectar bats were captured.

Commercially grown bananas do not produce seeds, so don’t need pollination. However, throughout the world’s tropics, wherever bananas have been introduced, they quickly attract nectar-feeding bats. When allowed to ripen in gardens, bananas also attract several species of fruit-eating bats, but loss to hungry bats is easily prevented by simply bringing stalks of bananas indoors prior to ripening.

When looking for fruit-eating bats, Merlin’s team had learned to enquire about the locations of wild fig trees bearing ripe fruit. A single large tree could produce a ton of figs, fruits that are virtually irresistible to many bats. Often, such trees could be found by simply tracing the calls of howler monkeys, toucans, or parrots, all of which love figs, though bats are, without a doubt, the most effective dispersers of figs.

Acquiring and accurately recording a collection of 114 species of mammals in less than nine weeks was exhausting, though afternoon swims in the adjacent lagoon at least alleviated the misery of heat and humidity.

Fortunately, team members didn’t discover the presence of a large crocodile neighbor till after several weeks of bathing without incident. The croc was spotted by its brightly reflective eye shine as Merlin, Fred, and Sido returned in the dugout canoe from a late evening of bat collecting. The six-inch or so space between its eyes confirmed it as large enough to be scary, before it mysteriously sank beneath the surface. But, given the weeks of peaceful co-existence and assurances that no attacks on local people had been reported, team members were simply more mindful, knowing they were sharing their site.

It was with mixed feelings that they finally began preparing for a return to civilization, though a bit of rest was urgently needed. Capitan Tex would pick them up with a pre-scheduled landing in the adjacent savannah, weather permitting. The two large expedition canoes were quickly sold. Equipment and specimens were shipped back down river to Puerto Ayachucho and flown separately to Caracas.

Merlin was eager to report to his mentor and boss, Dr. Charles Handley, Jr., at the Smithsonian, though he wasn’t surprised to run into a storm of threats from military side “bean counters.” Dr. Handley was elated to hear of amazing success. But military accountants were aghast! They announced that Merlin had broken virtually every rule possible, and charges would be filed. Perhaps a bit naive, Merlin found the threat somewhat amusing. With Dr. Handley’s help, they roughly calculated huge savings. His team had acquired more specimens and species in a single month than previous military-funded teams had obtained in a whole year. In fact, he and Dr. Handley calculated that, on-average, Merlin’s team had acquired specimens at a cost of just 75 cents each versus 10 dollars each for previously funded projects of similar size.

Dr. Handley assured Merlin of his 100% personal support, then smugly challenged his accusers with the facts. By breaking military rules, Merlin had achieved unprecedented success. Handley warned that he would fully back Merlin and that the news media would have a heyday. No further complaints were lodged. Dr. Handley declared Merlin a “natural born collector” and demonstrated his appreciation by playing a key role in gaining Merlin’s acceptance into a top graduate school program at the University of Kansas and later recommending him for the Curator of Mammals position at the Milwaukee Public Museum.

Merlin’s two years of field collecting leadership in Venezuela, Dr. Handley’s subsequent sponsorship, and a full-time research position in Milwaukee set the stage for the born collector to evolve into a consummate conservationist.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Bats can use sounds in many complex ways. They can sing and even have different dialects… When imagining a bat, the first thoughts that come

It was a long road to Austin, Texas. More than five years after my first introduction to Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation as a teenager, I packed

TEDx Talks recently released the video of Merlin Tuttle’s fascinating presentation about bats at TEDxUTAustin’s seventh annual conference, held on March 23rd. During his presentation,

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.