Challenging torrential rains countered by cooperative bats in Costa Rica

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Largely unnoticed, America’s bats have gradually become more and more stressed and vulnerable. As key hibernation shelters in caves and formerly abundant nursery roosts in ancient tree cavities were lost, bats had to spend more and more energy to survive. This left less for emergencies. So, when a fungus began to force costly winter arousals, many could no longer survive.

While scientists struggle to find a magic cure, a retired citizen volunteer, Kent Borcherding’s bat houses are showing impressive results.

Kent grew up on a Wisconsin farm where bird houses were popular. But, when he heard about bat houses in the early 1990s, he was intrigued. He became one of the first to conduct major experiments. And the more he learned about bats the more intrigued he became. Soon he was sharing his discoveries and making a real difference.

He unsuccessfully tested three bat houses in his yard (about a mile from the nearest river or lake)—no occupants after three years. However, undaunted he began testing bat houses in parks nearer lakes and rivers which supplied better feeding habitat. To his surprise, numbers of bats attracted seemed to be limited only by the number and size of houses he provided.

Kent found parks near lakes or rivers to be ideal locations. His bat houses would be protected indefinitely, with no fear of new homeowners not liking bats. The bats thrived on abundant food supplies. And park visitors especially appreciated the bats’ appetite for mosquitoes.

Perhaps most importantly, evening emergences from Kent’s bat houses became exciting attractions, providing outstanding opportunities for education. Kent’s interpretive signs put fear in perspective and instilled appreciation for bat values. He eventually installed more than 100 houses and has given nearly 200 bat talks and bat house building workshops. He’s still hard at work, providing both bat houses and lectures at 82, despite having been diagnosed with stage 4 cancer and given just three weeks to live a decade ago.

He credits his wife, Jane, and his passion for helping bats and people as his secret to longevity. With much to live for, he was successfully treated and is still building bat houses for parks and historic sites. He currently monitors 86 houses, mostly at two sites, 45 at Yellowstone Lake State Park and 41 at the Stonefield Historic Site near Cassville.

The best news is that, when quality summer homes are provided, and suitable feeding and hibernation sites are available, little brown myotis are showing clear signs of recovery. Counts on July 7 and 8, 2022, confirmed that numbers had grown remarkably in just three years. At the historic site in Cassville, they had increased six-fold from 400 to 2,500. And at Yellowstone Lake State Park numbers had grown from 270 to 921. Overall, Kent’s bat house dwellers have increased by a very encouraging 78%, illustrating how bats can once again thrive if provided with both summer and winter roosts and quality feeding habitat. (I am personally proud to have saved their apparent hibernation site in the abandoned Neda Mine decades ago.)

When asked what kind of bat house is best, Kent just grins and says, “The one that works best for you.” His houses are all black and exposed to full sun. However, that likely would be a recipe for failure in a warmer climate. Another unique modification includes a vent at the top of the first roosting chamber in the front of his multi-chambered houses. This increases air circulation and cooling and may be essential in preventing overheating of his black houses. Only local testing can reveal where such innovations may be useful.

Most of Kent’s houses have 4-5 roosting chambers, but both single and multi-chamber houses have been highly successful, especially when mounted in groups. He reports the main difference is the number of bats that can be accommodated.

He uses two-by-fours or two-by-sixes for sides and tops. This increases thermal stability and house lifespan. All roosting and landing areas have roughened surfaces. Furthermore, Kent’s houses are carefully caulked, sealed, and protected with three coats of paint. His 25-year-old houses are still in use! They also have roosting partitions (often referred to as baffles) that are easily removable. This permits replacement of any that are deteriorating.

Uniquely, he likes to install one baffle from a previously used house in each new one. He believes this encourages earlier occupancy. He often mounts houses on an 8-foot-long cross piece between two upright poles. This permits easier maintenance and attachment of multiple houses as a colony expands. Finally, he also uses a pulley system to hoist heavy houses into place.

Now that his bat houses have gone far beyond just having fun attracting bats and educating the people of Wisconsin, Kent is excited to see his houses playing an important role in restoring the animals he loves. Clearly, there’s potential beyond retirement!

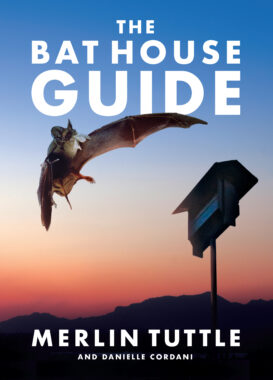

Kent Borcherding is a leading contributor to our new book "The Bat House Guide"!

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

“Just like the old days, eh Heather?” Kent softly clicks his tally counter as he sits in his folding chair on the other side of

Bats can use sounds in many complex ways. They can sing and even have different dialects… When imagining a bat, the first thoughts that come

It was a long road to Austin, Texas. More than five years after my first introduction to Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation as a teenager, I packed

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.