Why Don’t Bats Get Cancer? How bat research could transform human aging and cancer treatment…

Bats are the longest-lived mammals for their size, with species like the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) surviving over 30 years in the wild. Even

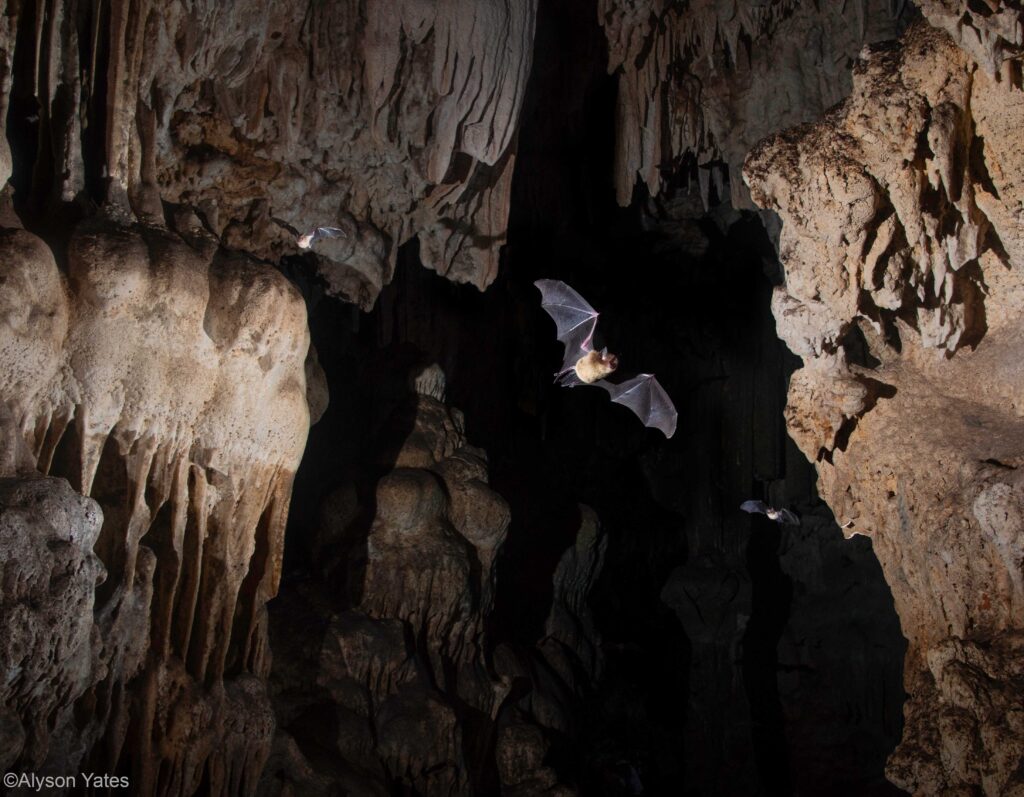

Within the dim limestone passageways of Caverna Santa Catalina, the air came alive with bats. I stood in awed silence, taking in the rush of leathery wings, the gentle breeze created by their wingbeats, and the occasional patter of guano falling onto my caving helmet. I impatiently waited for at least a few bats to strike my infrared beam, triggering carefully positioned flashes to record some of the thousands of bats heading out to feed.

I had set up a flight photography beam in a narrow section, hoping to illuminate the bats with motion-triggered flashes as they funneled past. After exhausting my camera’s battery (and my thumb’s strength on the shutter release), I was ecstatic to find that I had captured a beautiful image of a small mustached bat (Pteronotus sp?), in the right place at the right time. Even with so many bats, it’s often difficult to catch one in just the right position and location, not obscured by wings of other bats.

I had come to a workshop in Cuba, sponsored by Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation, with two objectives: to expand my bat research skills, and to learn new techniques for improved bat photography. As an environmental science graduate student and photographer interested in human-wildlife interaction, bats are a fascinating subject to explore. I first became captivated by these nocturnal mammals on an MTBC trip to Thailand in 2019, and in the years since, I have photographed bats at home and abroad. Bat photography has also given me valuable opportunities to connect with peers around the world. As an ambassador for the non-profit Girls Who Click, I have found a community of incredible women artists, scientists, and journalists working to educate and empower girls in nature photography. Their inspiration and mentorship have led me to unexpected places—like a humid cave in northwestern Cuba, where I sat snapping photos in the company of Cuban boas, tarantulas, and a few too many cockroaches.

Limestone caves like Caverna Santa Catalina are a Cuban national treasure, cherished by speleological groups and chiropterologists alike. These subterranean structures can be found all around the island—some have simple layouts with plain interiors, while others are mazes of complex passageways adorned with intricate crystals. Along with their geologic splendor, caves host a great diversity of organisms, including many species of bats. Thanks to the work of Cuban speleologists, many places like Caverna Santa Catalina have been preserved, along with the unique organisms that call them home.

As the city of Matanzas began to expand in the 1980s, this area was slated for conversion to a housing development. However, caving expeditions and 3-D imaging by the Comitè Espeleológico de Matanzas, the Speleological Group San Marco of Venice, and the Federazione Speleologica Veneta revealed a wealth of spectacular, glasslike features below the surface. These stunning images of the Bellamar caves convinced Cuban authorities to cancel their development plans and preserve the area in 2006.

Soon after, it was entrusted to the Antonio Núñez Jiménez Foundation for Nature and Humanity with the goal of promoting sustainable land use and education, resulting in the Jardines Bellamar permaculture project. Dozens of local families have since taken part in the project, planting thousands of native trees and cultivating organic produce. CUBABAT also conducts bat monitoring at Jardines Bellamar to better understand bat distribution and status trends in the region.

After a quick history lesson, we got to the task at hand: documenting the bats present at Jardines Bellamar through photography and data collection. While some of us prepared for flight photography or bat portraits, others assembled mist nets in locations around the property. As we waited for darkness to fall, I joined Yoel Monzón González, head coordinator of Proyecto CUBABAT, to gain some insight on the program and his work.

Since childhood, Yoel has been overflowing with questions about the natural world. Upon meeting cavers from the Sociedad Espeleológica de Cuba as a youth, he pleaded to join them on a caving expedition. At first they turned him away, saying that he was too young, but his persistence earned him a trip to Las Cuevas de Bellamar. The speleologists anticipated that the thousands of bats in the cave would frighten him. However, the opposite was true. Yoel returned from the passageway with a grin, cheering enthusiastically, “This is what I want to study!” The cavers just shook their heads—clearly there was no getting rid of him.

At just 14 years old, Yoel began learning everything he could about Cuban bats. He read hefty textbooks about bats and tried to catch bats using crab traps. He acquired a mist net from an ornithologist and gloves from a motorcycle rider. Now equipped with a scientist’s tools, Yoel began catching bats to study their characteristics. He continued his self-driven education until, nearly a decade later, he began learning about bats directly from chiropterologist Gilberto Silva Taboada. Yoel studied the distribution and movement of bats in many regions around Matanzas, and the results of his research started to influence the management of protected areas. But after years of working with other scientists to research Cuban bats, Yoel came to a disappointing realization. “They were working with bats, but nobody was actually focused on conservation,” he recounted. “After they got their data, they wouldn’t care what happened five years later.” And so, guided by that mission, Proyecto CUBABAT was born.

Since its inception, CUBABAT has focused on using education to change the way bats are perceived by Cubans. Their strategy revolves around the “triad of bat conservation,” based on the three main ecological functions that bats carry out: pollination of plants, dispersion of seeds, and consumption of pests. Yoel views this triad as fundamental to CUBABAT’s mission, primarily because these bat benefits can be visually proven. Farmers rely directly on these ecological functions, but they are usually not aware that they are facilitated by bats. “If you show them pictures of bats actually doing this work at night when they are sleeping, then they really appreciate the bats,” Yoel tells me.

Jardines Bellamar serves as a marvelous example of this strategy’s effectiveness. Every night, bats emerge from caves just below the surface and carry out the ‘triad’ of functions: pollinating important trees and shrubs, munching on fruits whose seeds are essential to reforestation, and gobbling thousands of insect pests, such as mosquitos. Crops that rely on these actions will be harvested by farmers, feeding families and boosting local economies, while the bats are provided with habitat and ample resources. In such a scenario, this relationship is reciprocal—humans and bats thrive in tandem.

When farmers begin to understand the values of bats, they become their strongest defenders. This is particularly important in Cuba, where many cave entrances are on private property. Some farmers are now so motivated to protect their bats that they only allow access to the caves with CUBABAT’s permission.

While Cuban farmers champion bats today, CUBABAT is also working to inspire the bat guardians of tomorrow. Yelenny Pacheco, environmental education coordinator for Proyecto CUBABAT, visits classrooms around the region, leading activities that teach kids about the importance of bats and why they shouldn’t be feared. CUBABAT sees immense potential in this community outreach, and intends to create a series of books to teach readers of all ages about bats. By educating young people about bat conservation, they hope to foster a culture that promotes acceptance and coexistence rather than fear and intolerance.

“Bats’ worst enemy is ignorance,” Yoel said. “That is why it is up to us to teach people, and through education, end the myths.”

Proyecto CUBABAT’s dedication to changing the public perception of bats is increasingly shared by additional organizations around the world, greatly aided by Merlin’s early inspiration. As people with a collective passion for bat conservation, we are united by the work we do and the message we share, regardless of international borders or language barriers. We need to learn from one another, lift each other up, and move forward together.

I feel honored to have contributed to the work of MTBC and CUBABAT during this adventure, but most of all, I am grateful to have experienced the truth of Merlin Tuttle’s favorite motto: win friends, not battles.

Thank you to fellow bat photographer Maria Serrano for translating during my interview with Yoel Monzón González!

About the author: Alyson Yates is a multimedia artist and science communication photographer based in Portland, Oregon. As a master’s student at Portland State University, she studies amphibian movement and applied road ecology in urban ecosystems.

Alyson began photographing bats in 2019 when she joined MTBC on a trip to Thailand, and she has continued to create images of bats and bat research in the western U.S. and beyond. Her other work as a contributing photographer for Oregon State University focuses on agriculture, natural resources, and education.

She is also an ambassador for Girls Who Click.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Bats are the longest-lived mammals for their size, with species like the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) surviving over 30 years in the wild. Even

Can we afford to lose bats? A recent study by Eyal Frank of the University of Chicago reveals that the dramatic decline in U.S. bat

Bats are among the most fascinating yet misunderstood creatures in the natural world, and for many conservationists, a single experience can ignite a lifelong passion

Many bat conservationists know that Kasanka National Park in Zambia is an exceptional place for bats, but it is also the place that sparked my

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Daniel Hargreaves is a lifelong bat conservationist who has worked globally to facilitate progress, including co-founding Trinibats, a non-profit bat conservation organization in Trinidad. He has organized and led field workshops worldwide, including five for MTBC. Following a long and successful career in business, he now manages a network of bat reserves for the Vincent Wildlife Trust in the UK, supervising research and development of new and innovative conservation techniques. Daniel also is one of the world’s premier bat photographers.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.