Discovering a Passion for Bats: Internships at Kasanka National Park

Bats are among the most fascinating yet misunderstood creatures in the natural world, and for many conservationists, a single experience can ignite a lifelong passion

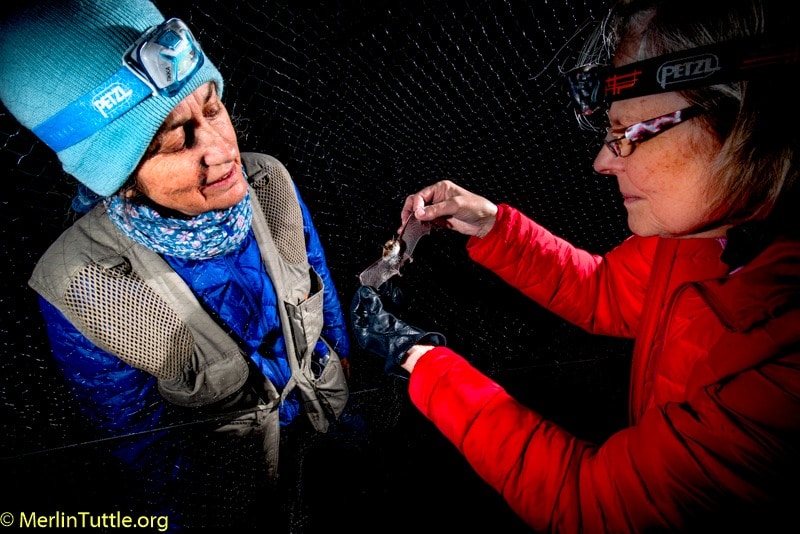

As MTBC’s Photo Collection Administrator, much of my responsibility lies behind a computer screen. I’d seen thousands (about 120,000 if we’re being real) of photographs from Merlin’s most-active field work days, preparing me for what to expect as much as photographs can. I’d seen mist nets, harp traps, banded bats, guano piles, and evidence of the bats’ incredible diversity.

Though fortunate to see Austin’s bats in a variety of ways, I’d never worked with bats first-hand. On this trip, I was most excited to step away from the desk and learn how bats are studied in the field, especially surrounded by knowledgeable and talented peers.

As with MTBC’s past adventures, our trip was a hands-on working trip with invaluable time and expertise contributed by leading colleagues from varied specialties. We were in the company of expert bat researchers, photographers, videographers, rehabilitators, consultants and passionate citizen scientists as we searched for some of the least known bats in the U.S.

Our Big Bend area expert, Loren Ammerman, senior author of the book, Bats of Texas, has been surveying bats in Big Bend National Park for more than 23 years. Her guidance contributed greatly to our success. Some of her favorite locations took hours to reach over unmaintained backroads.

One evening, we had to carry our equipment nearly three-quarters of a mile up a steep mountainside in a 30-mile-per-hour wind while temperatures dropped into the 40’s. We could count on Loren for a lot, but controlling the weather isn’t her forte!

Amazingly, no one complained, and though we only caught two bats that night, I would argue this was one of the most enjoyable evenings. Despite the cold wind keeping the bats away, the site and bumpy drive were quite special– something like I’d never before seen in Big Bend. We were in good spirits and around 2 AM, wrapped the evening up with camp-stove hotdogs (thanks for teaching me how to make hotdogs, Jeff Johnson). I never even heard complaints about our 3 AM return from the field.

One evening, we had to carry our equipment nearly three-quarters of a mile up a steep mountainside in a 30-mile-per-hour wind while temperatures dropped into the 40’s. We could count on Loren for a lot, but controlling the weather isn’t her forte!

One of our goals was to capture a spotted bat (Euderma maculatum). Only three had been caught in the Big Bend area in the past 20+ years. Spotted bats are arguably North America’s most spectacular but least-seen mammals. Loren hadn’t caught one in over five years despite numerous attempts. We can only speculate on why these bats are so hard to catch, but two possibilities are their scarcity and tendency not to fly low enough to encounter nets.

We also hoped to see the largest bat of the U.S. the western mastiff (Eumops perotis), well known to be an especially high flyer. In Merlin’s experience they only come low enough to be caught in a net set over water on exceptionally hot evenings.

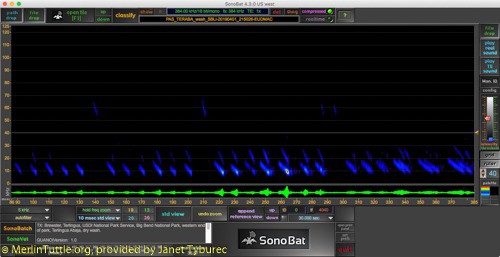

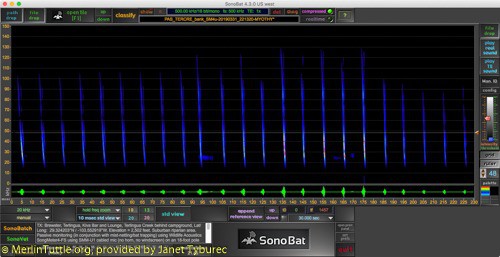

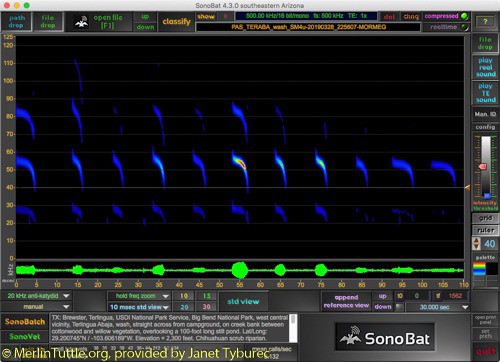

Thanks to Janet Tyburec’s bat-detector expertise, we were able to repeatedly identify spotted bats flying over-head at multiple locations and mastiffs at one, but unfortunately, we were unable to actually capture either, even when we attempted to attract spotted bats with sophisticated ultrasonic lures.

The first and warmest night was our best, resulting in 13 species captured, including one of America’s most fascinating mammals, the ghost-faced bat (Mormoops megalophylla). This incredibly strange bat has its eyes literally located in its ears.

Overall, despite the cold front, we captured 227 bats in just five nights, including beautiful hoary bats (Lasiurus cinereus) migrating north, some likely headed for Canada. We also caught the U.S.’s smallest (and exceptionally cute) canyon bats (Parastrellus hesperus), the rarely seen pocketed free-tailed bats (Nyctinomops femorosaccus), and the first two western yellow bats found in the Big Bend National Park since 1996, when the species was first recorded from Texas.

In addition to the 13 species we netted or trapped, Janet recorded the echolocation calls of four more, the spotted, mastiff, silver-haired (Lasionycteris noctivagans), and big free-tailed bats (Nyctinomops macrotis). In just five nights, our hard working team captured or recorded the calls of 17 species out of 24 likely to have been present during our visit.

Both canyon bats and pallid bats were unusually elusive on this trip. We were only able to catch four and five, respectively. Merlin had caught more than 100 pallid bats in one night at a Big Bend drinking site some 30 years ago, so their scarcity this time was a surprise. One of the pallid bats we did catch was unexpectedly covered in pollen at a time of year when there were no known bat-pollinated flowers blooming, raising the question of what it had found that we are unaware of.

Like humans, bats have unique personalities. One pallid bat remained calm and almost seemed to be smiling for photos, whereas the next one promptly closed its eyes and bared its teeth. Brazilian free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) are normally exceptionally calm and gentle. However, on this trip the two sexes behaved very differently. The males were calm as usual. But the females threw “tantrums” when netted. Merlin was quite surprised, but some in our group suggested, “They must be pregnant.”

John Chenger, founder of Bat Conservation and Management, was an invaluable source of technological and videographic expertise. Over the past year, he has been partnering with MTBC to shoot educational videos. Much of the content he shot on this trip will be incorporated into new programs.

Janet Tyburec was originally trained by Merlin in bat conservation and research techniques and is now a leading expert on ultrasonic identification of bats. She has 30+ years of experience teaching bat conservation workshops and has now taught over 3,000 students invaluable research and field techniques. For the past 15 years, she’s teamed up with John Chenger to provide a wide variety of bat conservation and management training.

Tyburec had been waiting decades to capture and record her first ghost-faced bat (Mormoops megalophylla). Her long-awaited goal was met within just hours on our first night. We ended up catching five at three different sites.

Nearby campers get curious when more than a dozen people show up with 20-foot-long poles with nearly invisible nets strung between them, start raising microphones high above ground, and even set up what appear to be large harps. At two locations we provided considerable entertainment as we welcomed campers, and on one cold night even shared hot chocolate with them.

It was great to see how excited our guests were to experience bats up close. Their eyes really lit up in response to Merlin’s famous story-telling. We were always glad to share our work.

They also were fascinated to see the varied techniques by which bats are photographed, especially Merlin with his portrait set-up and Daniel Whitby, a United Kingdom bat ecologist, using an infrared beam triggering device to catch them in flight as they were released. John Chenger and Teresa Nichta shot video to be used in new MTBC programs and I photographed everyone and everything, so that our participants could share their experiences.

Though faced with challenging weather, little sleep, and jarring roads, several participants declared their experience “the trip of a lifetime.” Reaching and setting up research stations required hours of rugged driving and carrying a seemingly endless assortment of equipment, but the scenery was unbeatable, and the team enthusiastic and full of fun.

Despite the challenges, Daniel Hargreaves, our U.K. bat-expert who played a key role in helping Teresa Nichta organize the trip, always had a smile to share, an encouraging word, and an offer to carry a larger load. We could expect a delicious breakfast each morning from Mindy Vescovo, Kathy Estes, and Jeff Johnson. Even through exhaustion, Roger Jones and Sally-Ann Hurry could be counted on for a laugh. The positive energy given from our participants was palpable. We could not have asked for a more appreciative and excited group of bat enthusiasts. I’d been to Big Bend National Park more times than I can count, but never quite like this.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Bats are among the most fascinating yet misunderstood creatures in the natural world, and for many conservationists, a single experience can ignite a lifelong passion

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Bats can use sounds in many complex ways. They can sing and even have different dialects… When imagining a bat, the first thoughts that come

Thanks to all the Join the Nightlife: Bats and Agriculture attendees who joined us out in the field this year! Guests got hands-on experience with

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.