Challenging torrential rains countered by cooperative bats in Costa Rica

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

The largest losses of cave-dwelling bats often occur prior to a cave’s discovery by cavers or bat biologists. When looking for bat roosts we simply ask about caves where bats currently live. And too often, those we discover are locations of last resort for bats that have been forced to abandon preferred sites. This presents major problems. The bats we see may be barely surviving in marginal conditions, misunderstood to be good or even ideal. Failure to recognize true needs can lead to disastrous conservation decisions.

For example, in northern Florida, lands located on the highest ground were the first to be developed, meaning that remaining caves, available for bats, tend to be in flood prone areas. Unaware of such risks, biologist Jeff Gore and I gained protection for Sneads Cave. It consisted mostly of just one large room, with a domed ceiling, good for trapping bat body heat, ideal as a nursery roost for southeastern myotis (Myotis austroriparious). The floor was covered in wet, rotting guano, making it exceptionally unattractive to humans and easy to protect. We just had to gain a landowner’s cooperation and post it with a sign. Some 20 years later, we were quite proud to have attracted a colony of roughly 250,000 bats.

However, when a severe hurricane flooded the area, the colony drowned. In hindsight, we realized we had lured these bats into a death trap.

Bat Cave in Missouri was designated and protected as critical habitat for endangered Indiana myotis (Myotis sodalis). And for decades the hibernating population grew steadily. Nevertheless, during a severe freeze the population crashed to near zero. When we installed temperature dataloggers, we quickly saw the problem. The cave’s huge entrance and main passage where bats hibernated was ideal for trapping cold air in the range needed. Nevertheless, the area was not sufficiently buffered from outside extremes, leaving the bats vulnerable to rare, but severe freezes.

Especially at hibernation caves in temperate areas, I’ve repeatedly observed similar problems. Bats ideally need caves large and complex enough to supply the widest range of temperature possible, enabling them to adjust safely in response to rare events or to climate change. Unfortunately, such caves were often the first to be converted to human use, and the huge bat populations that relied on them have long since been lost and forgotten. Today, most of America’s largest hibernating populations survive only where they have been discovered in abandoned mines that, as a result, have been protected.

There are still major opportunities to reestablish populations in caves that have not been used in the past century. Since bat researchers understandably work mostly only where bats still exist, organized cavers are the only ones likely to discover and report such caves, and they could play critical roles in restoring bat populations. Unfortunately, especially since the arrival of WNS in America, the needs and potentially critical partnership roles of cavers have too often been neglected. For decades, cavers have played a central role in reporting bats in need of protection and have designed, built, and managed bat-friendly gates that have restored many of America’s most important bat populations.

Large, complex caves are obviously those that should be checked first, though many still may not meet bat needs. Caves that have multiple entrances and chimney-effect air flow, i.e. “breath,” will have the widest range of temperature and should receive priority attention, especially ones that provide large dimensions at mid-latitudes. Summer colonies additionally need caves with relatively large entrances to minimize predation. At northern latitudes, even simple caves may support hibernation, and the reverse is true for nursery use in warmer southern areas.

Bracken Cave, in Central Texas, appears to violate the rules. It is a natural cold air trap used by the world’s largest remaining nursery colony. However, it is in a warm climate where minimal cold air can be trapped, and its 10 to 20 million Brazilian free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) easily heat it to an ideal nursery site temperature. Though chimney-effect “breathing” is often crucial at mid-latitudes, it is less important as one moves from north to south.

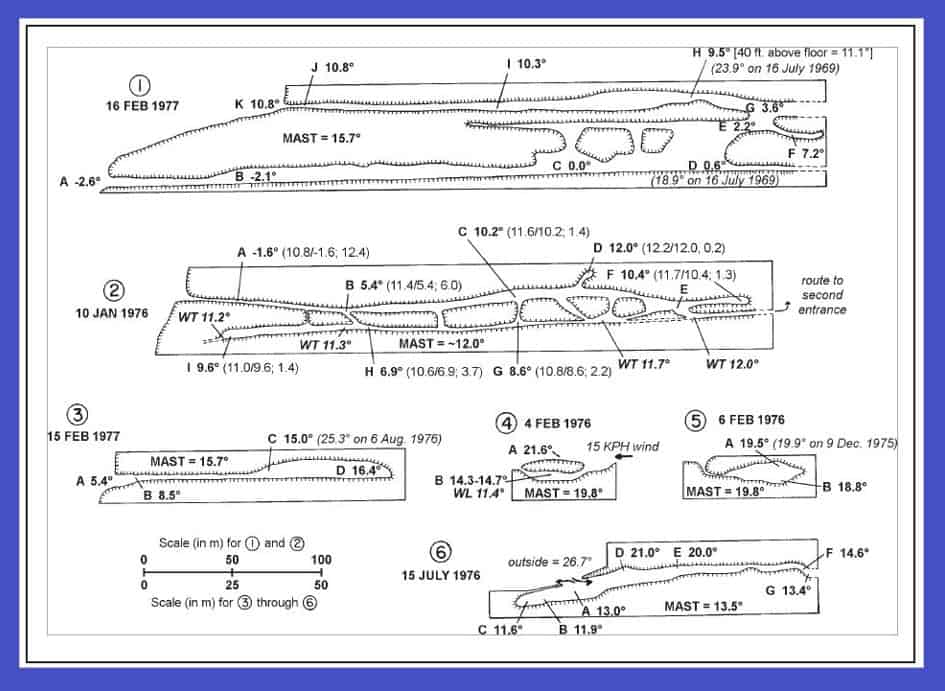

Figure 1 presents simple models illustrating how and when caves likely do or do not “breathe.” Cave “breathing” is typically strongest when outside temperatures deviate most, either above or below the mean annual surface temperature (MAST) for the area. Because these caves are sometimes located along remote ridgelines, it is quite possible that some major hibernation caves remain to be discovered. These might be found in time to protect them, if small planes equipped with thermal imaging cameras were used. Plumes of relatively warm air could be spotted most easily at night just after arrival of a severe fall cold front. For every cubic meter of warm air escaping, an equal amount of cold air must enter, thus these plumes can be used to help find cold trapping hibernation caves, assuming entrances are not located miles apart.

Air flow indicated as occurring in “winter” will generally occur when outside temperature is below mean annual surface temperature (MAST); flow marked “summer” will occur when outside temperature is above MAST. Type 1: Breathes (as indicated by arrows) in winter; stores cold air in summer. Type 2: Undulation at A acts as a dam inhibiting air flow; temperature is relatively constant beyond dam. Type 3: “Jug” shape often postulated to exhibit resonance; may have pulsing in and out air movement, especially when outside air deviates most from MAST (either summer or winter). Type 4: Strong air circulation from A to B in winter; traps cold air in summer (ideal for hibernating bats). Type 5: The reverse of Type 1; warm air enters along ceiling in summer while air cooled by cave walls flows out along floor. No flow in winter. X is a warm air trap, Y stays a relatively constant temperature. Type 6: Strong air flow from A to B in winter; equally strong air flow in opposite direction in summer. Type 7: Same as Type 6, with a warm air trap (X), cold air trap (Y), and an area of relatively constant temperature (Z). Distance between and elevational displacement of the entrances are critical factors in the air flow direction in these two cave types; the flow of air (cooled relative to outside temperatures by the cave walls) down in summer must be strong in order to overcome the tendency for warm outside air to rise into A. Similarly, in winter the “negative pressure” created by air (now warmer than outside air due to the MAST effect of the cave walls) rising out of B must be strong in order to pull cold air up into A.

Study of these models can help predict where roosting bats can be expected in different seasons.

Read here for a detailed explanation.

Today, most temperate-zone bats are unable to find ideal caves, especially for hibernation. They often are forced to use caves that are inadequately protected from human disturbance, provide less than ideal temperatures, and are not well buffered from periodically extreme weather events. They appear to survive costly hibernation by restricting themselves to a relatively few optimal summer locations near enough to marginal hibernation caves to survive by avoiding the cost of long migration.

Nursery roosts are typically located in heat-trapping domes, and the best hibernation roosts in caves are often found on vertical walls in “canyon passages.” Long used roosts normally show reddish brown stains when located on limestone. They are most evident at nursery sites. Temperature is a primary determinant of roost choice. Locations falling below 57° F (14° C) are rarely used as nursery roosts, and then only by species that form large clusters to share body heat.

Available evidence suggests that most bat species prefer to hibernate at roosts that provide relatively stable, low temperatures in areas that do not freeze. Several Myotis species, including Myotis grisescens, M. sodalis, and M. lucifugus, appear to prefer locations where early fall temperatures are between 46 and 50° F (8 and 10° C), with mid-winter temperatures between 35 and 45° F (2 and 7° C).

At northern latitudes, where mean annual surface temperatures are close to those required for bat hibernation, any cave or mine large enough to simply protect against freezing, may prove suitable. This is often the case in the Great Lakes Region where hundreds of miles of abandoned, hard-rock mine tunnels have gradually attracted millions of little brown myotis as they lost traditional hibernation caves.

Since these bats need caves only in winter, this may explain their continued pre-WNS abundance, as well as providing hope for recovery.

Farther south, the gray myotis, which is larger and more adaptable, appears capable of dominating suitable caves from northern Alabama to southern Kentucky. But it cannot extend its range either north or south due to its year-round dependence on caves, both cool ones for hibernation and warm ones for nurseries. Its largest populations occur where warm versus cool caves are closest together, minimizing migratory costs (Tuttle 1976). Such reduced costs permit hibernation at an exceptionally wide range of temperature.

The Indiana myotis, whose most important, traditional hibernation sites were in mid-latitude areas of Indiana, Kentucky, and Missouri (Tuttle and Kennedy 2002), lost its originally ideal caves to commercial tourism and apparently has been unable to reach northern mines in sufficient numbers to permit recovery.

Figure 2 contains rough sketches of real caves and the locations of bat roosts, again showing seasonal air flow, this time with actual recorded temperatures on specific dates.

Finding, protecting, and restoring bat caves, especially those used for hibernation, should be our highest priority in helping bats recover from devastating losses. It’s time to admit that we can’t stop or cure WNS. However, numerous opportunities to aid in recovery of resistant populations, especially of the endangered Indiana myotis, remain.

Disturbance and destruction of key roosting caves had already led to devastating losses of bats prior to the arrival of WNS (Barbour and Davis 1969, Tuttle 1997, Tuttle and Kennedy 2002). Hibernation site loss undoubtedly forced longer migrations, increased hibernation costs, and threatened Indiana myotis across multi-state regions (Hall 1962). It also may have made several species more susceptible to WNS.

The sudden loss of millions of additional bats has sent a much-needed wakeup call. However, efforts to restore dangerously depleted bat populations must not add additional harm. We must focus, first and foremost, on protecting bats from disturbance and on restoring key cave roosts, many of which have been long lost through human disturbance or alteration, but could be successfully restored.

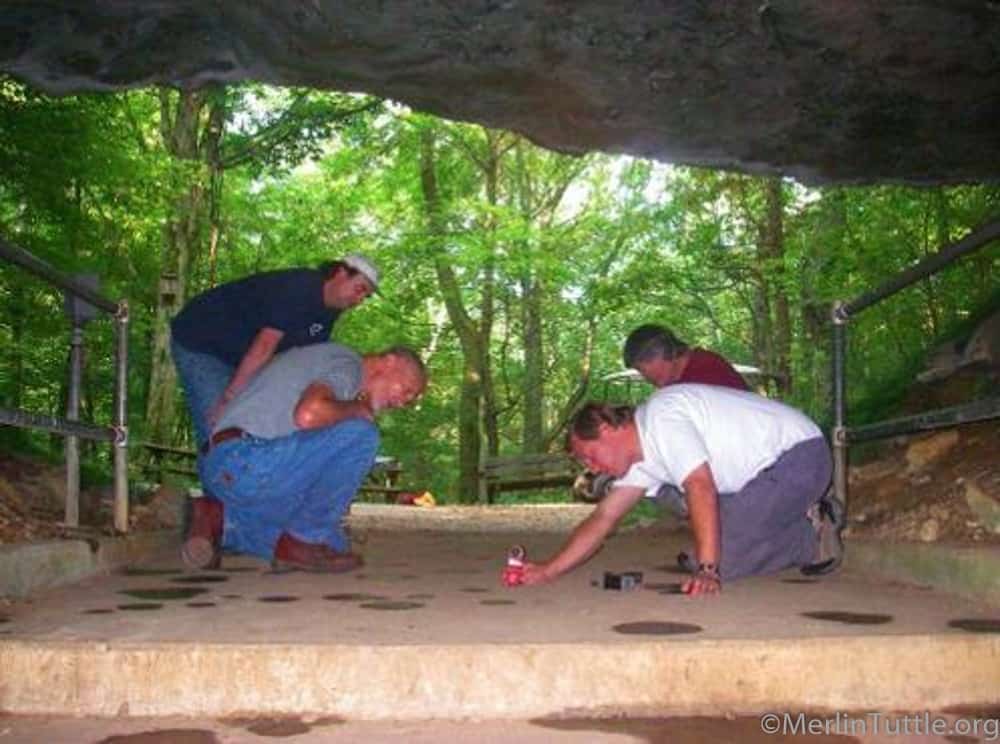

It is time to recognize this long-standing problem. At least two of the once greatest bat hibernation caves in America are already under federal and state control and should become top restoration priorities. Additionally, there are likely opportunities at other tour caves that are privately owned. Using remote, infrared cameras for viewing bats in special protected areas, bat education could provide added interest for visitors. My personal investigations suggest that progress could be dramatic, inexpensive, and minimally intrusive on existing tour use.

Finally, it may be time to consider artificial assistance at some locations. There are likely parts of tour caves, such as Mammoth, that could be partially sealed off with thermostat-controlled fans employed to aid restoration of needed cold air trapping. Even air conditioning may be feasible. The cost of such help would be minimal compared to that of keeping Indiana bats federally listed as endangered. And the public relations potentially gained by a company or agency willing to sponsor the challenge with mitigation funding could be well worth the effort.

There are numerous examples of remarkable success due to cave protection and restoration. As a result of cave disturbance and vandalism in the 1960’s and 70’s, the gray myotis’ (Myotis grisescens) extinction was predicted (Barbour and Davis 1969 and 1974). Yet, due to protection of the species’ most important roosting caves, today there are millions (Martin 2007).

Bibliography

Barbour, R.A. and W.H. Davis. 1969, Bats of America. Univ. Press of Kentucky, Lexington.

Barbour, R.A. and W.H. Davis. 1974. Mammals of Kentucky. Univ. Press of Kentucky, Lexington.

Hall, J.S. 1962. A life history and taxonomic study of the Indiana bat, Myotis sodalis. Reading Public Museum and Art Gallery, Scientific Publications 12:1-68.

Martin, C.O. 2007. Assessment of the population status of the gray bat (Myotis grisescens). Environmental Laboratory, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Wash. D.C. ERDC/EL TR-07-22.

Reeder, D.M., C.L. Frank, F.F. Turner, C.U. Meteyer, A. Kurta, E.R. Britzke, M.E. Vodzak, S.R. Darling, C.W. Stihler, A.C. Hicks, R. Jacob.

L.E. Grieneisen, S. A. Brownlee, L.K. Muller and D.S. Blehert. 2012. Frequent arousal from hibernation linked to severity of infection and mortality in bats with white-nose syndrome. PLOS one. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0038920 Relocate according to notes.

Tuttle, M.D. 1979. Status, causes of decline, and management of endangered gray bats. J. Wildl. Manage. 43(1):1-17.

Tuttle, M.D. 1997. A mammoth discovery. BATS 15(4):3-5.

Proc. Pp 108-121 in 1977 National Cave Management Symposium Proceedings (R. Zuber, J. Chester, S. Gilbert and D. Rhoades, eds.). Adobe Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

“Just like the old days, eh Heather?” Kent softly clicks his tally counter as he sits in his folding chair on the other side of

Bats can use sounds in many complex ways. They can sing and even have different dialects… When imagining a bat, the first thoughts that come

It was a long road to Austin, Texas. More than five years after my first introduction to Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation as a teenager, I packed

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.