Challenging torrential rains countered by cooperative bats in Costa Rica

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Everything doesn’t go so great all the time. We have our bad nights too. On our second night with bats in the studio, we shot 300 photos, most really good ones. Two nights ago we only got a few useful images, mostly because we were attempting an extremely difficult shot, namely bats in their final approach to flowers instead of actually at the flowers. This was more difficult than would normally be the case for nectar-feeding bats which routinely hover in front of flowers. These Pallid bats appear unable to hover and simply land on the flower. In so doing the wings are often in front of their faces, during the final approach.

To get that shot, we had to rig an infrared beam an inch in front of a flower then wait for long periods of time before our one bat who is working, La Contessa, would decide to visit the flower again. As the evening wore on she, of course, had filled her belly and had less incentive to visit. Because the beam has to be rigged to trigger flashes instead of cameras, in order to capture a split-second event, we had to shoot on bulb in very low light to prevent premature exposure. In the very low light, it is extremely difficult to tell when the bat is making a final approach to the flower, when often two to three bats would be circling nearby. The shutter had to be open just a split second prior to a bat breaking the beam as it approached the flower. The timing, combined with the low light and lack of visibility, made for many missed shots, complicated by the fact that, even when timing was correct, wings in front of faces often ruined even the best timed shots.

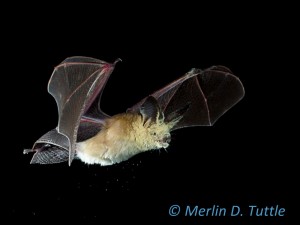

Here’s a short video clip of Merlin feeding mealworms to the bats: Merlin feeding pallid bats The one bat that did cooperate often completely drained the flower in a single visit and then wouldn’t be hungry again for another 30 minutes or more. Getting photos of our one cooperating bat departing from the flower with its face covered in pollen proved even more difficult, since after a Pallid bat lands on a flower to feed, there is absolutely no way to predict how soon it will depart. The camera shutter must be reopened after the bat lands, in order to catch its departure, but correct timing was a real challenge. With such difficult shooting, we only were able to get a half dozen good images in more than four hours of attempts. Merlin was so tired after three consecutive nights of working till 4 or 5 a.m., combined with weakness from his recent surgery, that at times he was performing about as effectively as if he had been drunk, slow reflexes and bumping into critically positioned beams and flash stands. Despite all that, Merlin got some nice flight shots of Pallid bats flying away from cardon flowers with pollen-covered faces.

On review today of photos so far taken, Merlin has concluded that all the critical project goals have been achieved, so we’re about to release the pallid bats, though some photography will continue.

On review today of photos so far taken, Merlin has concluded that all the critical project goals have been achieved, so we’re about to release the pallid bats, though some photography will continue.

Tonight we’ll only stay up late if Fred and Paul succeed in capturing a Western Yellow bat, a species which Merlin hopes to add to his portrait collection. The moon will be relatively bright tonight, and it’s not very hot today, so we’re not optimistic that they’ll be able to capture Yellow bats at their watering hole. We have mixed feelings: if they fail, we’ll get a night off, but Merlin also really wants a Yellow bat portrait.

Tomorrow night we’re hoping to photograph Lesser long-nosed and Pallid bats pollinating cardon cactus in the wild—a very big challenge!

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Merlin and MTBC team members spent 19 days in Costa Rica last November on a filming trip for “Bat City” with its Director and Emmy

Bats can use sounds in many complex ways. They can sing and even have different dialects… When imagining a bat, the first thoughts that come

Thanks to all the Join the Nightlife: Bats and Agriculture attendees who joined us out in the field this year! Guests got hands-on experience with

Supporter and friend of MTBC, Australian conservation and animal welfare photojournalist Doug Gimesy, had his images recognized in two categories at the recent Siena International

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.