The Gentle Side of Formidable Hunters: The Social Lives of Spectral Bats

Silent wings. Sharp teeth. A metre-wide wingspan cutting through the tropical night. The spectral bat (Vampyrum spectrum) is the largest carnivorous bat in the Americas

Caves are a critical resource for America’s bats. But thousands are no longer available for bats. Early American settlers relied on saltpeter from bat caves to produce gun powder. Then caves became lucrative for tourism, and many others were buried beneath cities or flooded by reservoirs. Even caves that were not destroyed often were rendered unsuitable for further bat use. Not surprisingly, the most cave-dependent bats quickly crashed to endangered status.

Today, nothing is more important to their recovery than identifying, restoring, and protecting key caves of past use. At that, Jim Kennedy is an unsung hero. Early in his career he joined me in critical research on the needs of cave-dwelling bats and worked with master bat-gate-building engineer, Roy Powers, to become an expert builder.

Kennedy became an expert at detecting evidence of past use by bats, and he has helped build gates to protect many of America’s most important remaining bat caves. He has also led workshops to train others. In 2013, he founded his own company, Kennedy Above/Under Ground, LLC. His teams have built 56 protective gates at 43 caves and abandoned mines where hundreds of thousands of bats have since recovered from severe losses.

Illustrative of the impact of protection at key locations, endangered gray bats at Bellamy Cave in Tennessee, increased from 65 to more than 150,000 once protected. And when a bad gate was replaced at Long Cave in Kentucky, gray bat numbers grew from zero to over 300,000. At Saltpeter Cave in Kentucky, endangered Indiana bats increased from zero to 7,000 when poor gates were replaced, air flow was restored, and winter visitor tours were terminated. Jim was involved in restoring each of these caves for use by bats.

Protection can be a real challenge. Even good gates, if wrongly located, can force abandonment partly because different species have unique needs. Gray bats, and other species that form large nursery colonies in caves, cannot tolerate full gates across entrances. Newly flying young slow down and become easy prey for predators. Jim has three ways of dealing with this. When a cave entrance is large enough, he leaves fly-over space above, relying on a perforated metal lip to prevent human entry. Alternatively, he sometimes builds a metal chute at the top, using perforated metal. When entrance size or shape precludes such approaches, he surrounds the entrance with a 10-foot-tall, perforated-steel fence. At Key Cave in Alabama, the Tennessee Valley Authority contracted Jim’s team early in 2021 to build a 390-foot fence that required 21 tons of steel. Its entrances were too small to permit young bats safe exit through gates.

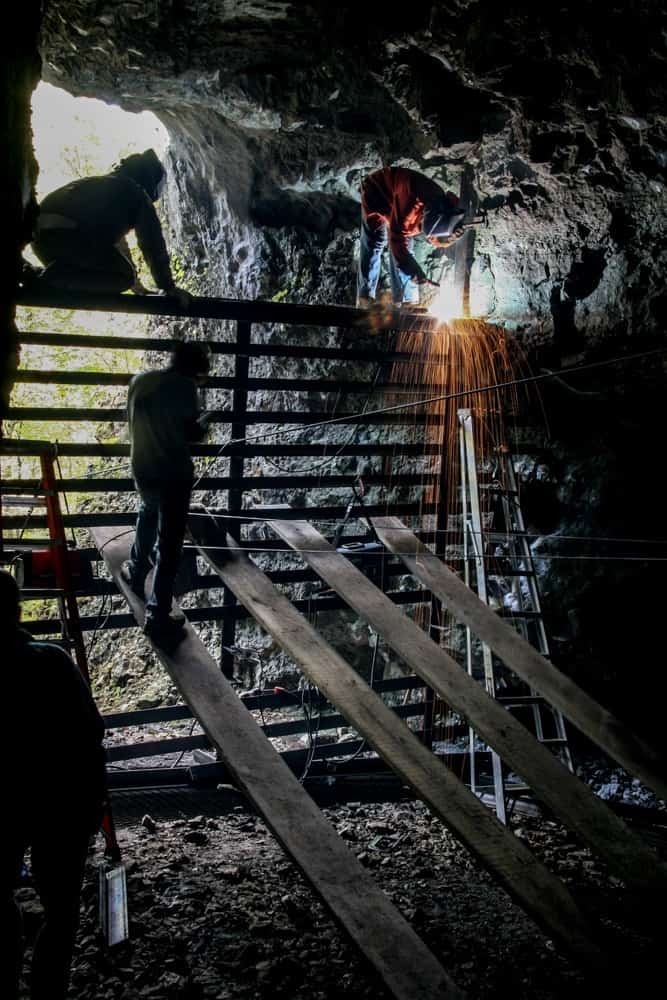

Cave entrances on cliff faces can be especially difficult. At Bat Cave in Missouri’s Mark Twain National Forest, the U.S. Forest Service contracted Jim and his team to haul tons of steel and equipment up a cliff face to gate the cave’s two entrances. A chute gate and a fly-over gate were necessitated to accommodate the cave’s gray bat nursery colony. For his success, Jim received a prestigious “Wings Across America” award.

In July 2020, Jim and his team encountered a new challenge when gating New York’s Barton’s Hill Mine. The 200-year-old mine includes miles of passages with multiple entrances at different levels, creating strong “chimney-effect” air flow. Though the gate was built in mid-summer, Jim’s team had to use a chain saw and jack hammer to remove ice that was blocking the work area. Then, despite summer heat, they were forced to wear snow mobile suits while working in a strong 38-degree Fahrenheit breeze exiting through the entrance!

This mine shelters the largest hibernating bat population in the Northeast, approximately 120,000 bats of at least four species. As bats have lost natural roosts in caves, abandoned mines have become increasingly important. In fact, they now shelter millions of displaced bats. This gate will protect both bats and humans. The ice-covered floor drops approximately 100 feet nearly vertically into a pool of water, a dangerous trap for the unwary. The Barton’s Hill Mine is now safer for both bats and people.

Protection and restoration of traditional, but long-lost hibernation sites may be the single most important option for restoring bats, especially those recently lost due to white-nose syndrome. Loss of key caves has forced millions of American bats to seek alternative shelter in less suitable locations where inappropriate temperature, and sudden shifts, can increase both the cost of rearing young in summer and that of hibernation in winter. This makes them less able to survive the stress of higher metabolic rates and forced arousals caused by white-nose syndrome and human disturbances. Furthermore, as the number of suitable roosting caves diminishes, bats are forced to expend more energy on longer travel between summer and winter roosts, leaving less and less for emergencies.

The value of protecting key cave roosts has already been proven for gray bats. When I began my conservation efforts on their behalf, nearly six decades ago, the species was in precipitous decline and America’s leading experts were predicting extinction. Today, due to the combined help of federal, state, and private organizations, volunteer cavers, and expert gate builders like the late Roy Powers and his protégée, Jim Kennedy, we have millions more gray bats than when their extinction was predicted. Nevertheless, additional cave-dwelling species, especially the endangered Indiana bat and little brown bat, remain in widespread need of help, and invaluable opportunities for restoration remain.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Silent wings. Sharp teeth. A metre-wide wingspan cutting through the tropical night. The spectral bat (Vampyrum spectrum) is the largest carnivorous bat in the Americas

Are you looking for gifts that delight bat lovers while supporting conservation and education? From beautifully illustrated picture books for young readers to behind-the-scenes storytelling,

Bats are often misunderstood, but a new book is helping change that. In The Genius Bat: The Secret Life of the Only Flying Mammal, neuroscientist

Our fourth annual Join the Nightlife workshop, held in Central Texas, brought together conservationists, researchers, and farmers from around the U.S. to explore the many

Daniel Hargreaves is a lifelong bat conservationist who has worked globally to facilitate progress, including co-founding Trinibats, a non-profit bat conservation organization in Trinidad. He has organized and led field workshops worldwide, including five for MTBC. Following a long and successful career in business, he now manages a network of bat reserves for the Vincent Wildlife Trust in the UK, supervising research and development of new and innovative conservation techniques. Daniel also is one of the world’s premier bat photographers.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.